Recently, enviroment minister Jairam Ramesh called Vapi the most polluted town in the country. Forbes and Time magazines have listed it among the 10 most polluted towns in the world. Its three life streams — Damanganga, Kolak and Balitha — no longer resemble a water body. The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) has in fact categorized both the Damanganga and Kolak rivers unfit to support life. The pollution has affected 71,000 residents living in 12 villages.

Forbes in 2008 wrote, “Vapi’s groundwater is reported to be polluted 96 times higher than the World Health Organization’s health standards; in addition, local agricultural produce can contain up to 60 times more heavy metals.” The nearby union territory of Daman is laying a Rs 47 crore pipeline from the Madhuban dam by next year to source water due to increasing pollution in Damanganga river.

On March 15 this year the director MoEF, S K Agarwal asked Gujarat to stop approving new factories in Vapi Industrial estate till August 2010, till issues are resolved. The town, which has 1,500 units, topped the list of 35 industrial clusters that were critically polluted in the Comprehensive Environmental Pollution Index. This was based on a report of the CPCB regarding the central effluent Treatment Plant (CETP) in Vapi which showed the treated outlet water on certain occasions was more polluted than the inlet from factories!

“The Vapi Industrial Association (VIA) and the CETP has failed to regulate its members. Critical values of chemical oxygen demand, biologicaloxygen demand, ammonical nitrogen, oil residues exceeded GPCB norms,” says environmental activist Rohit Prajapati.

Gujarat Pollution Control Board member secretary R G Shah says, “Illegal dumping of hazardous waste was a problem which we have tackled. In terms of CETP operations there is some improvement. It will take some time before we can say that Vapi is sanitized.”

“Due to expansions in several units the existing capacity of CETP treating 55 million litres a day (MLD) was increased to 70 MLD. Today, Vapi is reportedly being given an exclusive 16.5km deep sea pipeline to dispose 100 MLD of treated effluent into the sea,” says Vapi industrial association president Mahesh Pandya.

Source

Now the good news: Air pollution in Indian cities has been proved to be reversible, with improvements in public transport or changing over to greener fuels, reducing pollution levels.

But, now the really bad news: With industries being relocated to the peripheries of cities, growing urbanization and poor scrutiny outside big cities, small towns are emerging as India’s pollution hotspots.

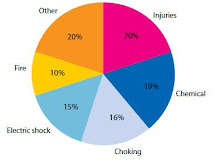

According to WHO estimates, roughly 0.1 million premature deaths annually can be attributed to air pollution. Exposure to air pollution causes both short-term and long-term health effects, from eye irritation and headaches to reduced lung capacity and lung cancer, with vehicular pollution being particularly harmful. The poor are the worst off, facing higher exposure and being unable to afford high healthcare costs. A 2005 World Bank report estimated that 13,000 lives and $1279 million were saved annually between 1993 and 2002 in five cities Delhi, Kolkata, Mumbai, Chennai and Hyderabad — as a result of measures taken to improve air quality.

A look at data for 2008 recorded by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) shows that Indian cities are choked. Of the 130 cities monitored, 70 have hit levels defined as critical for the presence of PM10, tiny particles of less than 10 microns in size regarded as the most dangerous pollutant as they can go deep into the lungs. However, the top five cities are Ludhiana, Khanna (both in Punjab), Ghaziabad, Khurja and Firozabad (all in UP). Delhi, the city where judicial activism for cleaner air has led to the ejection of polluting industries, comes in at sixth place.

The improvements in some major cities and the simultaneous emergence of several smaller towns as pollution hotspots shows that what we are seeing is national policy failure, says Anumita Roychowdhury, associate director of the CSE.

Northern India is far more polluted than the south, with Gobindgarh (Punjab), Kanpur (UP), Indore (MP) and Raipur (Chhattisgarh) rounding out the top-10 list. Some cities in south are showing rising PM10 trends — Hyderabad, Tuticorin, Bangalore and Coimbatore in particular. While particulate matter comes from a variety of sources, PM10 is largely from vehicles.

Eastern India, meanwhile, shows high levels of nitrogen dioxide which is fast emerging as a national challenge, according to the Centre for Science and Environment. In 1998, only five cities exceeded the national standards for presence of NO2. In 2008, 15 cities showed violations, most of them in eastern India: Howrah, Asansol, Durgapur and Kolkata have India’s highest NO2 levels. Increasing numbers of diesel cars, particularly in Delhi, is also a major cause of rising NO2 levels, according to the CSE.

The pollution control efforts in Indian cities show, however, that air pollution is not irreversible and this is not a lost battle. Public and judicial activism have resulted in eight cities — Delhi, Kanpur, Lucknow, Ahmedabad, Hyderabad, Bangalore, Chennai, and Sholapur being directly monitored by the Environment Pollution (Prevention and Control) Authority under Supreme Court orders. Mumbai and Kolkata are under the scrutiny of their high courts. According to a CSE report, Ahmedabad has reduced its PM10 levels by nearly 50%, Solapur (Maharashtra) by 57% and Chennai, Pune and Kolkata have stopped its growth.

Pollution levels have stabilized to some extent in some of these cities, but in the absence of aggressive action, these gains are in danger of being reversed. In Delhi, for example, the significant gains made from decades of public activism have been reversed and PM10, NO2 and ozone levels are rising fast according to CPCB data.

At the heart of the matter lies the fact that the bulk of pollution in Indian cities is caused by cars, and despite changes to greener fuels and improvements in public transport, direct curbs on number of cars on roads seems to be inevitable to manage pollution. In Delhi alone, 1100 vehicles are being added to the city’s five million every day, with car ownership growing at 10% annually since 1995.

Public ridership, meanwhile, has dropped from 60% in 2000-1 to 43% in 2008. In addition to investing in public transport, restraints on car ownership and usage are unavoidable if pollution is to be brought down to acceptable levels, says Roychowdhury.

Source

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment