Tuesday, November 18, 2008

Regulations on Occupational Safety & Health

Carsten Jöerges

Most countries try to reinforce Occupational Health and Safety (OSH) by implementing laws, which regulate the measures the companies have to take. So does India. Especially, the Factories Act, 1948, the Mines Act, the Ports Act and the Construction Act refer to safety of employees working in the respective sectors. For other employees, for example such as those employed in shops or establishments, various state legislations are enacted, which provide for almost similar matters as under the Factories Act.

In order to guarantee a sufficient level of OSH throughout the whole country, these Acts lay down very specific minimum requirements regarding health and safety. This way, differences between the single states in the administration of the Act can be minimised. Another intention of these detailed provisions is to facilitate the work of the inspectors who have to examine the conditions of work in the factories, which is said to require too much of expert knowledge of the inspectors.

In this report I wish to examine the problems these regulations cause. It would show possible alternatives to the regulation of OSH by the government. There are reasons for companies to provide safe and healthy workplaces to their employees without compulsion, and there are also examples of good practice.

Problems of Occupational Safety and Health Regulations

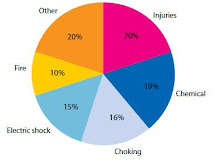

Despite comprehensive legislation, the number of accidents in India is very high. Takala estimates 36,740 fatal accidents in the year 1994, Smith goes up to 150,000 killed workers in 1993, whereas the official figure given by the Ministry of Labour is 1624. The difference between the figures results from the lack of reliability of reported numbers. The ILO report is based on the figures for Malaysia, Smith takes UK-figures and multiplies them with a (conservative) factor. However, they give strong evidence of the inefficiency of data collection in this realm.

This has either caused due to lack of enforcement; in this case any law would be useless. The number of Health and Factory Inspectors in India is far too small. For example, for the NCT of Delhi, there are only three Factory Inspectors. They were in charge of 6496 factories covered by the Factories Act at the end of 1999. That is not even one Inspector per 2000 factories, whereas a reasonable ratio would be one per 250, i.e. 24 Inspectors in all. Due to this scarcity of staff, regular visits to companies are virtually impossible, and inspectors react only when complaints are lodged or accidents are reported. Moreover, these few Inspectors are badly equipped. E.g. the sole X-ray machine of the Office of the Labour Commissioner had been defective since 1999, therefore X-ray examinations of workers could not be carried out.

The other reason for lack of enforcement could be the unsuitability of the centrally drafted regulations to the local situation in the factories. Legislations are either unrelated to the danger or do not take into account distinctive work situations. Obviously, workplaces differ from each other. Legislation, which neglects these differences, imposes very high costs on some workplaces, while others still remain unsafe, despite complying with the requirements. For example, the Factories Act requires minimum space for each worker to prevent overcrowding— 14.2 cubic metres for factories built after the commencement of this Act and 9.9 cubic metres for older ones. The actual checking of this requirement is carried out by the Health Inspector based on the building plan of the facility. The total available space is divided by the number of workers, so that violations for single workplaces cannot be found out.

Furthermore, the levied penalties are insignificant. Inspectors are in conflict between being too easy on firms and bankrupting them. Especially in poor areas, where unemployment plays an important role, the Inspector would not only consider the health of the employers, but also the security of their workplaces. The expected costs of non-compliance with legislation (the product of fine and probability of being convicted) therefore would be small compared to the expenses of improving the working conditions.

And lastly, it takes time to formulate legislation in response to constantly changing technologies. Laws would only be made, when safety problems have already occurred. Then they always would be some years behind the actual hazards.

In any case, only eight percent of the Indian workforce is employed in the organised sector; therefore the law necessarily will not reach the bigger part of it.

Why should companies provide sufficient safety and health measures without regulations by the state?

Regardless of the fact that many employers might feel a moral responsibility for their employees, there are economic reasons for them to prevent accidents and occupational diseases in their factories. I would like to focus on these economic reasons, for moral feelings are not measurable. A profit-maximising entrepreneur as an employer has to take expenses for OSH as an investment. He has to pay for possible revenue (the avoidance of costs) in the future. The consideration of the employer is simple: if the costs of accidents and illnesses exceed the expenses on OSH, it would be profitable to invest in further measures.

The costs of accidents or diseases

It is obvious that hazardous and unhealthy workplaces result in costs for the employer. The treatment of the injured or sick worker has to be paid for. If the worker is not able to resume work after his recovery, a substitute has to be trained and it will take some time before the new worker reaches the productivity levels of the old one. Indemnification for injured workers or those who have died and their families can cause considerable expenses; and the burden would be especially high for small and medium scale firms. In most cases the damage to workers is accompanied by damages to instalments which have to be repaired.

All these expenses can be easily assigned to the incident that causes them. Therefore they are direct costs. But what about the indirect costs? Workers who cannot work amount to a loss of production for the company. Other employees could be substitutes for them, but then the substitute would have to work overtime, which would be more expensive. If however, the substitution were to take place within the routine of a workday, it means that there has to have been an inefficiency before, for the aim of normal production should be a capacity utilisation close to 100%. This spare capacity causes overhead costs and contradicts the assumption of profit maximisation. Furthermore, equipment involved in an accident would have a shorter lifespan and would have to be replaced earlier.

Most companies could profit by publicising the production conditions in their factories/workplaces. Customers in developed countries often set a high value to the conditions under which products are fabricated. Moreover, a plant is not a closed system. Workers are part of the public, and with their incomes they are, more or less directly, customers of the company. Other companies provide facilities to carry out repair work, and transport finished goods outside the plant area. Companies, which do not maintain well co-ordinated safety measures, would therefore not only endanger their own employees but also others that co-ordinate their activities with the company. For these reasons hazardous workplaces would amount to a loss of image and finally, of sales.

All these costs are indirect and usually not registered as emerging from particular incidents, but they are the main part of costs arising due to unsafe working conditions. Estimates of the proportion between direct and indirect costs of accidents range from 1:1 to 1:20, depending on the considered sector and the methodology of recording. That means that the indirect costs are at least as high as the direct ones and, though more difficult to measure, it would be a criminal mistake to neglect them.

The costs of OSH

Estimates of costs of OSH measures tend to overestimate the actual costs. Examinations of the used methodologies of cost projection show that they are frequently overstated. Only the direct costs obvious to prevention of accidents and diseases are taken into account. This way usually consists of installing additional devices to separate the workers from the hazards. This not only impedes the flow of work but is also uneconomic. In most cases slight changes in the construction of installations would be more effective, cheaper, and they would involve the worker and his knowledge in the process of finding a better solution.

Furthermore, the installation of new machines (which is automatically done in the normal process of replacement) would not only enhance safety but also frequently increase the productivity.

Approaches to regulate OSH on free markets

Economic incentives vs regulations

Most countries try to improve OSH by regulatory measures through labour laws. But aren’t there more effective ways to reach this aim? For instance, economic incentives in this realm have several advantages over regulations.

First, in countries like India, where enforcement of existing labour laws is lax, firms tend to ignore regulations on OSH. Signals from markets cannot be ignored. Second, regulations prescribe a minimum level of OSH measures. Once this level is reached, there is no reason for further improvement. Economic incentives do not stop at a certain level. Third, the adaptation of laws to new risks takes time. Economic incentives apply to new hazards as they applied to the old ones. And fourth, economic incentives measure the outcome of OSH, not the means. Regulations prescribe certain means, which are intended to be effective.

Standards on OSH

Standards decided are consensus agreements between delegations representing all the economic stakeholders concerned - suppliers, users, employees and, often, governments. They agree on specifications and criteria to be applied consistently in the classification of materials, the manufacture of products and the provision of services.

Standards are one way to set a certain level without fixing minimum requirements. Almost every country has its own standards body: India has a Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS), in the United States there is the American National Standards Institute (ANSI). They publish standards in order to respond to customer demands, who want a certification from their suppliers for certain aspects like product quality or environmental protection. The best known standards are ISO 9000 for quality management, and ISO 14000 for environmental protection, both by the International Standardisation Organization (ISO), Geneva. These can be used for voluntary certification of implemented management systems in order to distinguish one company among its competitors, or, if most of the competitors already are certified, not to fall behind in the rat race.

OSH is another realm where standards could be applied. The widespread adoption of standards for OSH means that the workplace conditions in companies, which satisfy these standards, would be more attractive for workers and employees and the company would get a greater variety to choose the best from.

The above mentioned ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 comprise aspects of OSH only on the margin. ISO 9001 obliges the employers to communicate to the organisation the importance of meeting statutory and regulatory requirements, and environmental issues only go along with the safety of plants and machinery. A particular ISO standard on OSH does not exist and is not being planned, for differences in local values, culture, and requirements do not allow one sole standard suitable for all.

Therefore some countries have developed standards on Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems (OHSMS) according to their needs. A management system does not mean a specified set of restrictions or rules, which have to be followed. What is important is continual improvement of the working conditions. Improvements are not to be made isolated from other measures. With an OHSMS, OSH interests are considered to be equal to production, sales, or other fields of operation.

Currently the most discussed approach has been developed by a group of 13 European certification companies and the British Standardisation Institute (BSI). The Occupational Health and Safety Assessment Series (OHSAS) 18000 correspond to the structure of ISO 14000 and thus can be implemented without conflicts where this is already being used. India has published IS 15001: 2000 Indian Standard on Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems— Specification and Guidance for Use, which is based on OHSAS 18000 and adapted to the Indian needs.

IS 15001, similar to the other standards, names four phases of the improvement process: planning, implementation and operation, measurement and evaluation (checking and corrective action in OHSAS 18001), and management review.

Essential is the risk assessment process, which is described comprehensively in Annex C of IS 15001. It comprises of six steps: Classifying work activities, identifying hazards, determining risks, deciding if risk is tolerable, preparing risk control action plan, and reviewing adequacy of action plan.

Small companies are not required to go through the entire procedure of risk assessment that is described in IS 15001. They should carefully select which risks they would like to assess in detail. Information overkill on trivial risks that cannot be properly processed would lead to losses of important facts.

The ends are to resolve problems between OSH and other objectives, and the integration of OSH into the overall business management process. Improvements should not be of the type to be made once and never questioned again, but should be constantly revised and evaluated.

Good Practices

Maurya Sheraton & Towers

The ITC Hotel Maurya Sheraton & Towers, Delhi, has started implementing an OHSMS in 1995. For this purpose, it used guidelines for an OHSMS developed by the ITC group itself. Subsequently, Maurya Sheraton underwent the 5-Star Health and Safety Management System Audit instituted by the British Safety Council and conducted by their accredited auditors during the years 1995, 1996, and 1997. Each year a five star rating was achieved, and the hotel was awarded a Sword of Honour for each of those three successive years, thereby acknowledging it to be amongst the safest companies across the world. Besides a very good result of this certification, the loss prevention report for the last six years has showed a clear downward trend in the number of incidents and lost man-hours.

Improvements have included the training of every employee in safety matters, and the planning and arrangement of all facilities with regard to safety enhancement. Every employee can make a proposal of improvements, and everyone is responsible for safety in his realm.

New Zealand

Compliance with OHSMS standards does not by itself confer immunity from legal obligations. Therefore standards can only work if the legislation pays regard to the efforts of companies to certify their OHSMS. New Zealand's legislation on OSH, the Health and Safety in Employment Act (HSE), 1993, has committed the employers to prevent harm to the workers by taking appropriate measures. It is up to the employer how to achieve this. But how to measure whether the taken efforts were sufficient?

One means to make sure that the measures as sufficient is to maintain an implemented Occupational Health and Safety Management System. The used OHSMS can be measured with OSH standards. Therefore, New Zealand's standards body, Standards New Zealand, developed and published NZS 4801 (Int): 1999 Occupational health and safety management system— Specification with guidance for use. Again, this standard was developed to be compatible to ISO 9000 and ISO 14000.

Companies, which certify their efforts of implementing an OHSMS, can avail of discounts on their insurance fees at the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC). For these discounts the workplace has to be audited by an independent certification company, which decides whether the workplace qualifies for them. These discounts vary from ten to twenty percent, depending on the extent of conformation with the specified requirements of the ACC. After two years, the company has to reapply for continuing discounts. Indeed, the ACC has been the sole provider of accident insurance in New Zealand since July 1, 2000, but that doesn't mean that a free insurance market would fail to provide such discounts. Advice shows that in the years before free insurance market, fatalities had gone down between 25 and 50 percent.

The Occupational Health and Safety Service (OSHS) of New Zealand enforces the Act by carrying out proactive workplace visits, 17,969 in 2000. These visits resulted in 8,814 investigations. 127 prosecutions were finally initiated.

Though the number of complaints requiring OSHS investigation have increased during the last years (obviously the awareness for OSH matters has been enhanced), the number of prosecutions has been reduced due to a significant increase in compliance with the HSE Act, with many more companies managing their hazards better than in the past.

Conclusions

New Zealand has started a promising approach to give more flexibility to companies regarding their OSH measures. Nevertheless, inspectors of the OSHS have to judge whether the efforts taken are sufficient. Once again, only the means, not the results are being considered.

A solution for better performance of OSH could be the strict liability of the employer for accidents at work, attended by the commitment for insurance. This presupposes that the legislation on OSH has to be limited to these two aspects.

Insuring companies by giving discounts or raising the premium can affect the cost, depending on the hazardousness of the work place, to the company. This would bring about the identification of workplace hazards and of solutions on how to remove them. Instead of spending money on useless safety measures, the employers could decide for themselves how to improve the safety (and with it the attractiveness) of their workplaces.

Employers would endeavour to get these discounts, while insurance companies, which differentiate between them could attract good risks. Furthermore, insurance companies could provide information on the hidden costs of accidents.

References

Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC): Workplace Safety Management Practices. http://www.acc.org.nz/employers/workplace-safety.html 2001

Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS): Occupational Health and safety Management systems - Specification and Guidance for use, IS 15001:2000. New Delhi 2000

Charm, Joel B: Models already abound, in: Should there be an occupational health and safety management system standard? American Society for Quality, QEHS Zine http://www.asq-eed.org/qehs/april2000/procon.htm 2001

Dorman, Peter: The Economics of Safety, Health, and Well-Being at Work: An Overview. International Labour Organisation http://www.ilo.org/public/english/protection/safework/papers/ecoanal/ecoview.htm, Geneva 2000

Insurance Council of New Zealand: CTU Evidence To Select Committee Misleading Media release on http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PO0002/S00055.htm , February 16, 2000

International Standardisation Organisation (ISO)

Labour Laws

Landau, Kurt: Ergonomie im Dienstleistungsbetrieb, Berlin 1985

Occupational Safety and Health Service (OSH): What we've achieved: The OSH Annual Report 2000. http://www.osh.dol.govt.nz/touch/more/annrep00.html 2000

Office of the Labour Commissioner, Planning and Statistical Cell, Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi: Labour Statistics 1999- 2000

Polachet, Solomon W.; Siebert, Stanley: Compensating wage differentials and heterogeneous human capital, in: The Economics of Earnings. Cambridge University Press 1993

Smith, Stirling: Occupational Safety and Health in India: an attempt to estimate the real number of work related deaths. http://www.lsi.org.uk/indiaosh.shtml , November 1999

Takala, Jukka: Global estimates of fatal occupational accidents. International Labour Organization http://132.236.108.39:8050/public/english/protection/safework/accidis/globesti.pdf , Geneva 1998

The Factories Act, 1948 Universal Law Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., Delhi

more

Constitutional Provisions

CHAPATER-III

SUGGESTIONS TO IMPROVE OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH IN THE WORK PLACES

3.1 National Policy on Occupational Safety and Health

A coherent national policy on occupational safety and health of workers employed in all sectors of the economy should be prepared. This policy would serve as guidelines for all government departments, enforcement agencies, employers and employee organizations as well as other organizations to take appropriate measures to promote occupational safety and health.

The policy need to be framed through tripartite consultation among the Government, employer’s representatives and representatives of the employees.

3.2 General Legislation on Occupational Safety and Health

A general legislation to secure the safety and health of persons at work as well as other persons, against the risk arising out of or in connection with activities at places of work should be enacted. This legislation should be applicable to factories, mines, plantation, ports, construction, unorganized sectors and also to such categories of workplaces or work activities as may be notified by Central Government or by National Board on OSH on behalf of the Central Government.

3.3 Apex body on Occupational Safety and Health

An Apex Body on Occupational Safety and Health under the Ministry of Labour should be constituted. The members on the body shall be drawn from the Ministries of Govt. of India, Employers organizations and Employees organizations. The size of the board should be limited to 15-20 members. The representatives of professional organizations of repute could be co-opted as members on the board.

In order to carry out its activities efficiently and effectively, the Body may constitute various councils , committees and sub-committees for specific purposes/activities.

3.4 New Initiatives for the mining sector

Mines safety management in India has its own paradigm for safety. The present strategies place safety responsibility with a staff coordinator who is isolated from the line function and more often than not is given the task of finding out hazards by means of inspections, etc. This approach fails to integrate safety into the organization, thereby limiting its ability to identify and resolve management oversights that contribute to accident causation. Activities employed in traditional safety programs are frequently “post vention” - that is, heightened activities after an incident, and with time returning to activity level prevailing prior to the incident. For the mining sector of the country a new safety management system need to be formulated through extensive discussions at a national level among all concerned players in the field.

3.4.1 Suggested measures for the future

An approach based on a combination of “strategic” and “systems” thinking has to be devised to prepare the whole of mining industry in order to achieve greater heights as far as safety and health of persons employed in mines are concerned. The new thinking must embrace organizational, behavioral and cultural systems on top of hazard control, analysis to anticipate hazards and engineering solutions to prevent accidents.

Improvement in productivity with enhanced safety as a consequence, as an objective and as a balance through safety auditing should be the safety policy of the industry. In this context, considering the Government policies regarding downsizing and optimum utilization of existing manpower, and understanding the fact that expansion of the Mines Inspectorate can only be upto a certain degree, it will be a necessity to consider external third party safety audit systems for assessing status of safety in Indian mines. The Ministry of Labour have taken some steps in this area and an amendment of Mines Act proposal is being considered by the government which proposes accreditation of external private auditors for mine safety audit.

3.4.2 Role Of The Mines Inspectorate (DGMS)

The government, employers and workers have clear responsibilities for health and safety in the working environment.

According to the ILO international instruments, the prime responsibility for the health and safety of workers in their employments rests with the employers. The employer should provide and maintain a safe and healthy working environment, ensure the provision of occupational safety and health services to workers, and give a high priority to health, safety and the work organization in general in order to reduce the incidence of occupational injuries and diseases. The employer plays an essential role in the performance of occupational health practice. To ensure its success, the employer should allocate the necessary resources, demonstrate his desire for workers to participate in the implementation of occupational health programme and be willing to accept suggestions from occupational health specialists on its successful implementation.

Under the scenario explained in the preceding paras, the role of Inspectorates (in present instance – DGMS) become ever more important. It is the Inspectorate who can bridge the gap between the Employer and the Employee and formulate adequate guidelines for a better and safer workplace. All over the world, this is the role played by the respective Inspectorates. In USA, Mines Safety & Health Administration (MSHA); in UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE); in Australia different Departments of Minerals & Energy (DME); in South Africa the South African Inspectorate all play the same role. The situation is no different in any other country in the world whether developed or developing.

3.4.3 Training & Education Of Workers in mines

The important step to be taken is development of Standard Work Procedure or Safe Work Procedure (SWP) for every recognized, repetitive task that the mineworkers perform.

3.4.4 Strengthening Legal Set up of DGMS and Setting up of Designated Courts

Strengthening of the existing legal setup of DGMS for ensuring adequate attention in all such cases requiring redressal through the court of law would effectively offset the present problems of following up a case in the Courts of Law.

3.4.5 Strengthening of Mine Safety Enforcement Machinery

In order to bring about increased effectiveness it will be necessary to re-structure and rationalize functioning of DGMS for optimal utilization of the existing resources, replacement of human efforts through automation and planning and prioritization of inspection before proposing the bare minimum increase in strength of the inspectorate.

3.4.6 Making ISOs Effective

It is essential that the Internal Safety Organisations are suitably strengthened with adequate responsibility coupled with required authority.

3.4.7 Third Party Auditing

Safety audits have proved to be a very effective tool for assessing and eventually for improving safety and health conditions in mines. Considering paucity of resources in the form of adequate manpower in DGMS, recourse could be taken to a system of third party audits by accredited mining experts.

3.4.8 Risk Management

Introduction of risk management as a tool for development of a good health and safety management system is a break through in the traditional strategy. The system is an effective tool for improvement of safety and health scenario.

3.4.9 Users to pay for services rendered

With liberalization of economy and need for the Government to generate revenue, it will be necessary for DGMS to charge the users for services rendered. Traditionally till present times, a host of services are provided by DGMS to the mining industry, manufacturers of mining equipment and others related to the industry free of charge. Statutory permissions for extraction of minerals are granted, approvals are given for the mine safety equipment, assessment of safety status in mines are taken up, certificates are granted to competent persons for supervising and managing a mine, sample tests are carried out for ascertaining quality of some products used in mines, training courses are conducted for the benefit of particular categories of officials and workers, occupational health audits are taken up, etc. All these services are aimed at enhancing safety and health of workers and their workplace. Time has now arrived when the Government must consider charging the users for all these very important services. Suitable schemes need to be drawn up for the purpose.

3.5 Strengthening and restructuring of DGFASLI

In order to enhance the competence of officers regular in-service training in the field of their activities should also be arranged. Competence enhancement through participation in training programmes, seminars, workshops, presentation of papers, publication of technical documents should be considered as essential parameter for career advancement of the officers.

In order to increase effectiveness and efficiency in the services offered by Labour Institutes under DGFASLI, complete autonomy should be given to these institutes. This will also facilitate generation of adequate funds for self-sustainment of their activities through plough back of these funds. A task force to study the problems in depth and device a mechanism for giving this autonomy should be constituted.

Opportunities should be created for exposure of DGFASLI officers in developed countries to the latest techniques in the field of occupational safety and health. For this purpose a plan scheme should also be prepared.

3.5.1 Coordination of Administration of Factories Act

Extensive training of factory inspectors should be undertaken by organising programmes at state level or regional levels. For this purpose a plan scheme could also be prepared. Alternatively, a component on training of inspectors of factories should be added to any new plan scheme being proposed.

Standards for inspection of factories, including procedure and check-lists should be prepared. These standards should be made available to all state factories inspectorates. Training programmes for use of these standards by inspectors could also be organised.

Codes of practices on occupational safety and health for use by industries in selected areas such as noise, handling of chemicals, ship breaking, etc. should be prepared and published. Video films, manuals, booklets, should also be prepared and distributed amongst industries.

Submission of information in FAS forms to DGFASLI by the state factories inspectorates should be made mandatory by incorporating suitable provisions under the Factories Act 1948 or through Regulations.

A task force should be constituted to review and simplify the information to be furnished in FAS Forms.

3.5.2 Enforcement of Dock Workers(Safety, Health & Welfare) Act 1986

All port trusts and employers should appoint qualified safety officers as per the statutory requirements.

All State Governments should be directed to notify the Dock Workers (Safety, Health and Welfare) Rules in respect of other ports. Alternatively these can be notified by Central Government.

Dock Safety Advisory Committee constituted by Ministry of Labour should be enlarged to include representatives from some of the other ports.

3.5.3 Education and Training of factory and dock workers

The minimum qualification for admission to the Diploma Course in Industrial Safety should be upgraded to Graduate in Engineering or Post graduate in Science.

All institutions conducting diploma course in industrial safety/any other course in the field of safety and health, which are prescribed as essential qualifications for appointment as professionals in factories/ports as per the statutes, should be recognised by the Apex Body on OSH.

All safety officers, factory medical officers, industrial hygienists appointed/to be appointed in factories and ports should be accredited/registered with the Apex Body on OSH.

The syllabus at college/university levels especially in the areas of science, technology and medicine should be modified to include topics of safety and health. Efforts should be made in medicine field and engineering field to introduce a compulsory subject in field of occupational health and occupational safety with the help of Indian Medical Council/University Grants Commission/All India Council of Technical Education.

Public awareness about health hazards due to environmental pollution, diseases due to exposure to harmful substances should be created through mass media. Booklets, pamphlets, leaflets etc. should be prepared and distributed amongst the industrial/port workers for creating awareness. For this purpose, a component in the proposed plan schemes for the Xth Plan should also be included, seeking cooperation/participation of organizations specialized in the field of safety, health and environment.

A short-term course (15 – 30 days) should be designed and conducted for the medical doctors in government, semi-government, ESI hospitals for increasing their awareness and competence in diagnosis of occupational diseases. This will also enable them to report the suspected cases of occupational disease to authorities concerned in time.

Regular training programmes on occupational health including the Certificate Course on Industrial Medicine should also be conducted at Regional Labour Institutes under DGFASLI.

In order to strengthen the OSH education and training and improving their quality and complete compliance with the spirit of the provisions of the Factories Act which place duties of the Occupier for providing suitable training to their workers and supervisors, there is need for development of Model Guidelines for Approval of Training Centres/Institutes by CIFs as required under Section 111-A of the Factories Act, Development of Model Curriculae and Manuals of Training Courses for key categories of workers (such as those employed in hazardous processes and dangerous operations) and Development of Educational Modules on OSH for inclusion in the syllabi of the Engineering colleges.

3.5.4 Consultancy studies and services

Institutions and professionals rendering consultancy services in the field of occupational safety and health should be recognised at national level by Apex Body or any other agency made responsible for that purpose.

Private laboratories, or laboratories attached to technical institutions should be encouraged to undertake consultancy services in the field of workplace environment monitoring, health monitoring etc. These laboratories should be registered/accredited by the Apex Body or any other agency appointed by Apex Body for that purpose.

Existing facilities at CLI, RLIs, NIOH, ITRC should be upgraded to the level of National Referral Laboratories.

3.5.6 Participation of NGO/other organisation in activities of DGFASLI

For undertaking national level studies and surveys, DGFASLI should seek cooperation in the form of facilities, manpower and financial resources from employers organizations/associations.

National level workshops, seminars and specialized training progammes should be conducted in collaboration with NGOs and professional organizations such as NSC, LPA, OISD, BIS etc.

Local level awareness programmes and promotional programmes should also be arranged by DGFASLI for spreading the safety and health message amongst general population. This should be done in collaboration with local level community bodies/industries, association/NGOs.

3.5.7 State Inspectorates of Factories

In order to bring in the uniformity and to strengthen the status of Chief Inspector of Factories for making decisions in matters of safety and health, the Chief Inspector of Factories should be selected from amongst the cadre of Inspectors of Factories. He should be given the status of the Head of Department in the state.

The system of appointing medical practitioners particularly those working in either government/government aided hospitals or even private practitioners as certifying surgeons for carrying out the activities as envisaged under the provisions of the Factories Act should also be adopted by states. However, nominated certifying surgeons should be adequately trained in the field of occupational health.

All officers of Inspectorates of Factories at local level and regional level should be provided with basic infrastructure such as Cellular Telephone, Residence telephone, computer, fax and transport. Networking of local and regional officers should also be established for easy and quick transfer of information from one office to another.

Online submission of statutory forms, compliance reports and other statutory information by occupiers of the factory should be facilitated. For online dissemination of information regarding new developments, circulars, directives and changes in rules and regulations, these information should be placed on the web-site of the inspectorates of factories.

In order to bring in uniformity in approach and coordination amongst various departments of State Government, such as: Office of Labour Commissioner, Department of Environment, State Pollution Control Board, Electrical Inspectorate, Public Health Department, Employees State Insurance & Workmen Compensation Department, Fire Brigade and Boiler Inspectorate, there is a need for a state level committee on occupational safety and health comprising of representatives from these departments as well as department of Industry, Employers Association and Employees Association.

A national committee under proposed Apex Body on Occupational Safety and Health on control of occupational diseases may be constituted. The Occupational Disease Centres established by the ESI Corporation, occupational Health Centres established by different public sector undertakings, large public hospitals and Industrial Medicine/Occupational Health Laboratories at CLI, RLIs, NIOH and ITRC should be net-worked for diagnosis and prevention of occupational diseases, and sharing of information.

3.5.8 Safety and health in small and intermediate ports

Dock Workers (Safety, Health & Welfare) Rules and Regulations should be immediately notified by all State Governments.

Enforcement of these rules/regulations should be entrusted to existing enforcing authorities such as Chief Inspector of Factories/Department of Port under State Governments.

Training programmes in the areas of safety and health in dock work should be conducted for the benefit of dock workers, employers and port officials of small, intermediate and private ports.

3.5.9 Site Appraisal/Environmental Clearance

Concept of single window clearance for approval of factories/sites from safety, health and environment, pollution, as required under various statutes enforced by state governments should be adopted. A competent authority/committee should be established for this purpose.

3.6 Occupational Safety and Health Management System

In order to reduce burden of inspection on Inspector of Factories, a system of self regulation should be encouraged for adoption by management of industries. The guidelines issued by ILO and BIS standard IS: 15001 should be adopted by factories. Management of factories should be encouraged to get their OSH MS certified by accredited auditors from time to time. In order to ensure proper implementation of OSH MS management should appoint Safety Officers, safety observers in addition to statutory requirements.

3.6.1 Safety and health performance and insurance premium

Factories showing excellency in safety performance or certified OSH MS should be given rebate/incentive in insurance premium under ESIC schemes.

3.6.2 Statement on Status of OSH in Company’s Annual Report

Companies should include in their Annual Report a resume on the OSH measures adopted. This can be made statutory requirement if felt necessary.

3.6.3 There is also need for creation of an independent national level accrediation agency of eminent professionals for establishment of national standards on OSH and development of an audit mechanism for assessing effectiveness of OSH in industries, ports and mines by external safety audits.

3.7 Suggested measures for improvement in unorganized sector

This has been discussed in details in Chapter:IV.

more

Most countries try to reinforce Occupational Health and Safety (OSH) by implementing laws, which regulate the measures the companies have to take. So does India. Especially, the Factories Act, 1948, the Mines Act, the Ports Act and the Construction Act refer to safety of employees working in the respective sectors. For other employees, for example such as those employed in shops or establishments, various state legislations are enacted, which provide for almost similar matters as under the Factories Act.

In order to guarantee a sufficient level of OSH throughout the whole country, these Acts lay down very specific minimum requirements regarding health and safety. This way, differences between the single states in the administration of the Act can be minimised. Another intention of these detailed provisions is to facilitate the work of the inspectors who have to examine the conditions of work in the factories, which is said to require too much of expert knowledge of the inspectors.

In this report I wish to examine the problems these regulations cause. It would show possible alternatives to the regulation of OSH by the government. There are reasons for companies to provide safe and healthy workplaces to their employees without compulsion, and there are also examples of good practice.

Problems of Occupational Safety and Health Regulations

Despite comprehensive legislation, the number of accidents in India is very high. Takala estimates 36,740 fatal accidents in the year 1994, Smith goes up to 150,000 killed workers in 1993, whereas the official figure given by the Ministry of Labour is 1624. The difference between the figures results from the lack of reliability of reported numbers. The ILO report is based on the figures for Malaysia, Smith takes UK-figures and multiplies them with a (conservative) factor. However, they give strong evidence of the inefficiency of data collection in this realm.

This has either caused due to lack of enforcement; in this case any law would be useless. The number of Health and Factory Inspectors in India is far too small. For example, for the NCT of Delhi, there are only three Factory Inspectors. They were in charge of 6496 factories covered by the Factories Act at the end of 1999. That is not even one Inspector per 2000 factories, whereas a reasonable ratio would be one per 250, i.e. 24 Inspectors in all. Due to this scarcity of staff, regular visits to companies are virtually impossible, and inspectors react only when complaints are lodged or accidents are reported. Moreover, these few Inspectors are badly equipped. E.g. the sole X-ray machine of the Office of the Labour Commissioner had been defective since 1999, therefore X-ray examinations of workers could not be carried out.

The other reason for lack of enforcement could be the unsuitability of the centrally drafted regulations to the local situation in the factories. Legislations are either unrelated to the danger or do not take into account distinctive work situations. Obviously, workplaces differ from each other. Legislation, which neglects these differences, imposes very high costs on some workplaces, while others still remain unsafe, despite complying with the requirements. For example, the Factories Act requires minimum space for each worker to prevent overcrowding— 14.2 cubic metres for factories built after the commencement of this Act and 9.9 cubic metres for older ones. The actual checking of this requirement is carried out by the Health Inspector based on the building plan of the facility. The total available space is divided by the number of workers, so that violations for single workplaces cannot be found out.

Furthermore, the levied penalties are insignificant. Inspectors are in conflict between being too easy on firms and bankrupting them. Especially in poor areas, where unemployment plays an important role, the Inspector would not only consider the health of the employers, but also the security of their workplaces. The expected costs of non-compliance with legislation (the product of fine and probability of being convicted) therefore would be small compared to the expenses of improving the working conditions.

And lastly, it takes time to formulate legislation in response to constantly changing technologies. Laws would only be made, when safety problems have already occurred. Then they always would be some years behind the actual hazards.

In any case, only eight percent of the Indian workforce is employed in the organised sector; therefore the law necessarily will not reach the bigger part of it.

Why should companies provide sufficient safety and health measures without regulations by the state?

Regardless of the fact that many employers might feel a moral responsibility for their employees, there are economic reasons for them to prevent accidents and occupational diseases in their factories. I would like to focus on these economic reasons, for moral feelings are not measurable. A profit-maximising entrepreneur as an employer has to take expenses for OSH as an investment. He has to pay for possible revenue (the avoidance of costs) in the future. The consideration of the employer is simple: if the costs of accidents and illnesses exceed the expenses on OSH, it would be profitable to invest in further measures.

The costs of accidents or diseases

It is obvious that hazardous and unhealthy workplaces result in costs for the employer. The treatment of the injured or sick worker has to be paid for. If the worker is not able to resume work after his recovery, a substitute has to be trained and it will take some time before the new worker reaches the productivity levels of the old one. Indemnification for injured workers or those who have died and their families can cause considerable expenses; and the burden would be especially high for small and medium scale firms. In most cases the damage to workers is accompanied by damages to instalments which have to be repaired.

All these expenses can be easily assigned to the incident that causes them. Therefore they are direct costs. But what about the indirect costs? Workers who cannot work amount to a loss of production for the company. Other employees could be substitutes for them, but then the substitute would have to work overtime, which would be more expensive. If however, the substitution were to take place within the routine of a workday, it means that there has to have been an inefficiency before, for the aim of normal production should be a capacity utilisation close to 100%. This spare capacity causes overhead costs and contradicts the assumption of profit maximisation. Furthermore, equipment involved in an accident would have a shorter lifespan and would have to be replaced earlier.

Most companies could profit by publicising the production conditions in their factories/workplaces. Customers in developed countries often set a high value to the conditions under which products are fabricated. Moreover, a plant is not a closed system. Workers are part of the public, and with their incomes they are, more or less directly, customers of the company. Other companies provide facilities to carry out repair work, and transport finished goods outside the plant area. Companies, which do not maintain well co-ordinated safety measures, would therefore not only endanger their own employees but also others that co-ordinate their activities with the company. For these reasons hazardous workplaces would amount to a loss of image and finally, of sales.

All these costs are indirect and usually not registered as emerging from particular incidents, but they are the main part of costs arising due to unsafe working conditions. Estimates of the proportion between direct and indirect costs of accidents range from 1:1 to 1:20, depending on the considered sector and the methodology of recording. That means that the indirect costs are at least as high as the direct ones and, though more difficult to measure, it would be a criminal mistake to neglect them.

The costs of OSH

Estimates of costs of OSH measures tend to overestimate the actual costs. Examinations of the used methodologies of cost projection show that they are frequently overstated. Only the direct costs obvious to prevention of accidents and diseases are taken into account. This way usually consists of installing additional devices to separate the workers from the hazards. This not only impedes the flow of work but is also uneconomic. In most cases slight changes in the construction of installations would be more effective, cheaper, and they would involve the worker and his knowledge in the process of finding a better solution.

Furthermore, the installation of new machines (which is automatically done in the normal process of replacement) would not only enhance safety but also frequently increase the productivity.

Approaches to regulate OSH on free markets

Economic incentives vs regulations

Most countries try to improve OSH by regulatory measures through labour laws. But aren’t there more effective ways to reach this aim? For instance, economic incentives in this realm have several advantages over regulations.

First, in countries like India, where enforcement of existing labour laws is lax, firms tend to ignore regulations on OSH. Signals from markets cannot be ignored. Second, regulations prescribe a minimum level of OSH measures. Once this level is reached, there is no reason for further improvement. Economic incentives do not stop at a certain level. Third, the adaptation of laws to new risks takes time. Economic incentives apply to new hazards as they applied to the old ones. And fourth, economic incentives measure the outcome of OSH, not the means. Regulations prescribe certain means, which are intended to be effective.

Standards on OSH

Standards decided are consensus agreements between delegations representing all the economic stakeholders concerned - suppliers, users, employees and, often, governments. They agree on specifications and criteria to be applied consistently in the classification of materials, the manufacture of products and the provision of services.

Standards are one way to set a certain level without fixing minimum requirements. Almost every country has its own standards body: India has a Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS), in the United States there is the American National Standards Institute (ANSI). They publish standards in order to respond to customer demands, who want a certification from their suppliers for certain aspects like product quality or environmental protection. The best known standards are ISO 9000 for quality management, and ISO 14000 for environmental protection, both by the International Standardisation Organization (ISO), Geneva. These can be used for voluntary certification of implemented management systems in order to distinguish one company among its competitors, or, if most of the competitors already are certified, not to fall behind in the rat race.

OSH is another realm where standards could be applied. The widespread adoption of standards for OSH means that the workplace conditions in companies, which satisfy these standards, would be more attractive for workers and employees and the company would get a greater variety to choose the best from.

The above mentioned ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 comprise aspects of OSH only on the margin. ISO 9001 obliges the employers to communicate to the organisation the importance of meeting statutory and regulatory requirements, and environmental issues only go along with the safety of plants and machinery. A particular ISO standard on OSH does not exist and is not being planned, for differences in local values, culture, and requirements do not allow one sole standard suitable for all.

Therefore some countries have developed standards on Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems (OHSMS) according to their needs. A management system does not mean a specified set of restrictions or rules, which have to be followed. What is important is continual improvement of the working conditions. Improvements are not to be made isolated from other measures. With an OHSMS, OSH interests are considered to be equal to production, sales, or other fields of operation.

Currently the most discussed approach has been developed by a group of 13 European certification companies and the British Standardisation Institute (BSI). The Occupational Health and Safety Assessment Series (OHSAS) 18000 correspond to the structure of ISO 14000 and thus can be implemented without conflicts where this is already being used. India has published IS 15001: 2000 Indian Standard on Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems— Specification and Guidance for Use, which is based on OHSAS 18000 and adapted to the Indian needs.

IS 15001, similar to the other standards, names four phases of the improvement process: planning, implementation and operation, measurement and evaluation (checking and corrective action in OHSAS 18001), and management review.

Essential is the risk assessment process, which is described comprehensively in Annex C of IS 15001. It comprises of six steps: Classifying work activities, identifying hazards, determining risks, deciding if risk is tolerable, preparing risk control action plan, and reviewing adequacy of action plan.

Small companies are not required to go through the entire procedure of risk assessment that is described in IS 15001. They should carefully select which risks they would like to assess in detail. Information overkill on trivial risks that cannot be properly processed would lead to losses of important facts.

The ends are to resolve problems between OSH and other objectives, and the integration of OSH into the overall business management process. Improvements should not be of the type to be made once and never questioned again, but should be constantly revised and evaluated.

Good Practices

Maurya Sheraton & Towers

The ITC Hotel Maurya Sheraton & Towers, Delhi, has started implementing an OHSMS in 1995. For this purpose, it used guidelines for an OHSMS developed by the ITC group itself. Subsequently, Maurya Sheraton underwent the 5-Star Health and Safety Management System Audit instituted by the British Safety Council and conducted by their accredited auditors during the years 1995, 1996, and 1997. Each year a five star rating was achieved, and the hotel was awarded a Sword of Honour for each of those three successive years, thereby acknowledging it to be amongst the safest companies across the world. Besides a very good result of this certification, the loss prevention report for the last six years has showed a clear downward trend in the number of incidents and lost man-hours.

Improvements have included the training of every employee in safety matters, and the planning and arrangement of all facilities with regard to safety enhancement. Every employee can make a proposal of improvements, and everyone is responsible for safety in his realm.

New Zealand

Compliance with OHSMS standards does not by itself confer immunity from legal obligations. Therefore standards can only work if the legislation pays regard to the efforts of companies to certify their OHSMS. New Zealand's legislation on OSH, the Health and Safety in Employment Act (HSE), 1993, has committed the employers to prevent harm to the workers by taking appropriate measures. It is up to the employer how to achieve this. But how to measure whether the taken efforts were sufficient?

One means to make sure that the measures as sufficient is to maintain an implemented Occupational Health and Safety Management System. The used OHSMS can be measured with OSH standards. Therefore, New Zealand's standards body, Standards New Zealand, developed and published NZS 4801 (Int): 1999 Occupational health and safety management system— Specification with guidance for use. Again, this standard was developed to be compatible to ISO 9000 and ISO 14000.

Companies, which certify their efforts of implementing an OHSMS, can avail of discounts on their insurance fees at the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC). For these discounts the workplace has to be audited by an independent certification company, which decides whether the workplace qualifies for them. These discounts vary from ten to twenty percent, depending on the extent of conformation with the specified requirements of the ACC. After two years, the company has to reapply for continuing discounts. Indeed, the ACC has been the sole provider of accident insurance in New Zealand since July 1, 2000, but that doesn't mean that a free insurance market would fail to provide such discounts. Advice shows that in the years before free insurance market, fatalities had gone down between 25 and 50 percent.

The Occupational Health and Safety Service (OSHS) of New Zealand enforces the Act by carrying out proactive workplace visits, 17,969 in 2000. These visits resulted in 8,814 investigations. 127 prosecutions were finally initiated.

Though the number of complaints requiring OSHS investigation have increased during the last years (obviously the awareness for OSH matters has been enhanced), the number of prosecutions has been reduced due to a significant increase in compliance with the HSE Act, with many more companies managing their hazards better than in the past.

Conclusions

New Zealand has started a promising approach to give more flexibility to companies regarding their OSH measures. Nevertheless, inspectors of the OSHS have to judge whether the efforts taken are sufficient. Once again, only the means, not the results are being considered.

A solution for better performance of OSH could be the strict liability of the employer for accidents at work, attended by the commitment for insurance. This presupposes that the legislation on OSH has to be limited to these two aspects.

Insuring companies by giving discounts or raising the premium can affect the cost, depending on the hazardousness of the work place, to the company. This would bring about the identification of workplace hazards and of solutions on how to remove them. Instead of spending money on useless safety measures, the employers could decide for themselves how to improve the safety (and with it the attractiveness) of their workplaces.

Employers would endeavour to get these discounts, while insurance companies, which differentiate between them could attract good risks. Furthermore, insurance companies could provide information on the hidden costs of accidents.

References

Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC): Workplace Safety Management Practices. http://www.acc.org.nz/employers/workplace-safety.html 2001

Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS): Occupational Health and safety Management systems - Specification and Guidance for use, IS 15001:2000. New Delhi 2000

Charm, Joel B: Models already abound, in: Should there be an occupational health and safety management system standard? American Society for Quality, QEHS Zine http://www.asq-eed.org/qehs/april2000/procon.htm 2001

Dorman, Peter: The Economics of Safety, Health, and Well-Being at Work: An Overview. International Labour Organisation http://www.ilo.org/public/english/protection/safework/papers/ecoanal/ecoview.htm, Geneva 2000

Insurance Council of New Zealand: CTU Evidence To Select Committee Misleading Media release on http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PO0002/S00055.htm , February 16, 2000

International Standardisation Organisation (ISO)

Labour Laws

Landau, Kurt: Ergonomie im Dienstleistungsbetrieb, Berlin 1985

Occupational Safety and Health Service (OSH): What we've achieved: The OSH Annual Report 2000. http://www.osh.dol.govt.nz/touch/more/annrep00.html 2000

Office of the Labour Commissioner, Planning and Statistical Cell, Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi: Labour Statistics 1999- 2000

Polachet, Solomon W.; Siebert, Stanley: Compensating wage differentials and heterogeneous human capital, in: The Economics of Earnings. Cambridge University Press 1993

Smith, Stirling: Occupational Safety and Health in India: an attempt to estimate the real number of work related deaths. http://www.lsi.org.uk/indiaosh.shtml , November 1999

Takala, Jukka: Global estimates of fatal occupational accidents. International Labour Organization http://132.236.108.39:8050/public/english/protection/safework/accidis/globesti.pdf , Geneva 1998

The Factories Act, 1948 Universal Law Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., Delhi

more

Constitutional Provisions

CHAPATER-III

SUGGESTIONS TO IMPROVE OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH IN THE WORK PLACES

3.1 National Policy on Occupational Safety and Health

A coherent national policy on occupational safety and health of workers employed in all sectors of the economy should be prepared. This policy would serve as guidelines for all government departments, enforcement agencies, employers and employee organizations as well as other organizations to take appropriate measures to promote occupational safety and health.

The policy need to be framed through tripartite consultation among the Government, employer’s representatives and representatives of the employees.

3.2 General Legislation on Occupational Safety and Health

A general legislation to secure the safety and health of persons at work as well as other persons, against the risk arising out of or in connection with activities at places of work should be enacted. This legislation should be applicable to factories, mines, plantation, ports, construction, unorganized sectors and also to such categories of workplaces or work activities as may be notified by Central Government or by National Board on OSH on behalf of the Central Government.

3.3 Apex body on Occupational Safety and Health

An Apex Body on Occupational Safety and Health under the Ministry of Labour should be constituted. The members on the body shall be drawn from the Ministries of Govt. of India, Employers organizations and Employees organizations. The size of the board should be limited to 15-20 members. The representatives of professional organizations of repute could be co-opted as members on the board.

In order to carry out its activities efficiently and effectively, the Body may constitute various councils , committees and sub-committees for specific purposes/activities.

3.4 New Initiatives for the mining sector

Mines safety management in India has its own paradigm for safety. The present strategies place safety responsibility with a staff coordinator who is isolated from the line function and more often than not is given the task of finding out hazards by means of inspections, etc. This approach fails to integrate safety into the organization, thereby limiting its ability to identify and resolve management oversights that contribute to accident causation. Activities employed in traditional safety programs are frequently “post vention” - that is, heightened activities after an incident, and with time returning to activity level prevailing prior to the incident. For the mining sector of the country a new safety management system need to be formulated through extensive discussions at a national level among all concerned players in the field.

3.4.1 Suggested measures for the future

An approach based on a combination of “strategic” and “systems” thinking has to be devised to prepare the whole of mining industry in order to achieve greater heights as far as safety and health of persons employed in mines are concerned. The new thinking must embrace organizational, behavioral and cultural systems on top of hazard control, analysis to anticipate hazards and engineering solutions to prevent accidents.

Improvement in productivity with enhanced safety as a consequence, as an objective and as a balance through safety auditing should be the safety policy of the industry. In this context, considering the Government policies regarding downsizing and optimum utilization of existing manpower, and understanding the fact that expansion of the Mines Inspectorate can only be upto a certain degree, it will be a necessity to consider external third party safety audit systems for assessing status of safety in Indian mines. The Ministry of Labour have taken some steps in this area and an amendment of Mines Act proposal is being considered by the government which proposes accreditation of external private auditors for mine safety audit.

3.4.2 Role Of The Mines Inspectorate (DGMS)

The government, employers and workers have clear responsibilities for health and safety in the working environment.

According to the ILO international instruments, the prime responsibility for the health and safety of workers in their employments rests with the employers. The employer should provide and maintain a safe and healthy working environment, ensure the provision of occupational safety and health services to workers, and give a high priority to health, safety and the work organization in general in order to reduce the incidence of occupational injuries and diseases. The employer plays an essential role in the performance of occupational health practice. To ensure its success, the employer should allocate the necessary resources, demonstrate his desire for workers to participate in the implementation of occupational health programme and be willing to accept suggestions from occupational health specialists on its successful implementation.

Under the scenario explained in the preceding paras, the role of Inspectorates (in present instance – DGMS) become ever more important. It is the Inspectorate who can bridge the gap between the Employer and the Employee and formulate adequate guidelines for a better and safer workplace. All over the world, this is the role played by the respective Inspectorates. In USA, Mines Safety & Health Administration (MSHA); in UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE); in Australia different Departments of Minerals & Energy (DME); in South Africa the South African Inspectorate all play the same role. The situation is no different in any other country in the world whether developed or developing.

3.4.3 Training & Education Of Workers in mines

The important step to be taken is development of Standard Work Procedure or Safe Work Procedure (SWP) for every recognized, repetitive task that the mineworkers perform.

3.4.4 Strengthening Legal Set up of DGMS and Setting up of Designated Courts

Strengthening of the existing legal setup of DGMS for ensuring adequate attention in all such cases requiring redressal through the court of law would effectively offset the present problems of following up a case in the Courts of Law.

3.4.5 Strengthening of Mine Safety Enforcement Machinery

In order to bring about increased effectiveness it will be necessary to re-structure and rationalize functioning of DGMS for optimal utilization of the existing resources, replacement of human efforts through automation and planning and prioritization of inspection before proposing the bare minimum increase in strength of the inspectorate.

3.4.6 Making ISOs Effective

It is essential that the Internal Safety Organisations are suitably strengthened with adequate responsibility coupled with required authority.

3.4.7 Third Party Auditing

Safety audits have proved to be a very effective tool for assessing and eventually for improving safety and health conditions in mines. Considering paucity of resources in the form of adequate manpower in DGMS, recourse could be taken to a system of third party audits by accredited mining experts.

3.4.8 Risk Management

Introduction of risk management as a tool for development of a good health and safety management system is a break through in the traditional strategy. The system is an effective tool for improvement of safety and health scenario.

3.4.9 Users to pay for services rendered

With liberalization of economy and need for the Government to generate revenue, it will be necessary for DGMS to charge the users for services rendered. Traditionally till present times, a host of services are provided by DGMS to the mining industry, manufacturers of mining equipment and others related to the industry free of charge. Statutory permissions for extraction of minerals are granted, approvals are given for the mine safety equipment, assessment of safety status in mines are taken up, certificates are granted to competent persons for supervising and managing a mine, sample tests are carried out for ascertaining quality of some products used in mines, training courses are conducted for the benefit of particular categories of officials and workers, occupational health audits are taken up, etc. All these services are aimed at enhancing safety and health of workers and their workplace. Time has now arrived when the Government must consider charging the users for all these very important services. Suitable schemes need to be drawn up for the purpose.

3.5 Strengthening and restructuring of DGFASLI

In order to enhance the competence of officers regular in-service training in the field of their activities should also be arranged. Competence enhancement through participation in training programmes, seminars, workshops, presentation of papers, publication of technical documents should be considered as essential parameter for career advancement of the officers.

In order to increase effectiveness and efficiency in the services offered by Labour Institutes under DGFASLI, complete autonomy should be given to these institutes. This will also facilitate generation of adequate funds for self-sustainment of their activities through plough back of these funds. A task force to study the problems in depth and device a mechanism for giving this autonomy should be constituted.

Opportunities should be created for exposure of DGFASLI officers in developed countries to the latest techniques in the field of occupational safety and health. For this purpose a plan scheme should also be prepared.

3.5.1 Coordination of Administration of Factories Act

Extensive training of factory inspectors should be undertaken by organising programmes at state level or regional levels. For this purpose a plan scheme could also be prepared. Alternatively, a component on training of inspectors of factories should be added to any new plan scheme being proposed.

Standards for inspection of factories, including procedure and check-lists should be prepared. These standards should be made available to all state factories inspectorates. Training programmes for use of these standards by inspectors could also be organised.

Codes of practices on occupational safety and health for use by industries in selected areas such as noise, handling of chemicals, ship breaking, etc. should be prepared and published. Video films, manuals, booklets, should also be prepared and distributed amongst industries.

Submission of information in FAS forms to DGFASLI by the state factories inspectorates should be made mandatory by incorporating suitable provisions under the Factories Act 1948 or through Regulations.

A task force should be constituted to review and simplify the information to be furnished in FAS Forms.

3.5.2 Enforcement of Dock Workers(Safety, Health & Welfare) Act 1986

All port trusts and employers should appoint qualified safety officers as per the statutory requirements.

All State Governments should be directed to notify the Dock Workers (Safety, Health and Welfare) Rules in respect of other ports. Alternatively these can be notified by Central Government.

Dock Safety Advisory Committee constituted by Ministry of Labour should be enlarged to include representatives from some of the other ports.

3.5.3 Education and Training of factory and dock workers

The minimum qualification for admission to the Diploma Course in Industrial Safety should be upgraded to Graduate in Engineering or Post graduate in Science.

All institutions conducting diploma course in industrial safety/any other course in the field of safety and health, which are prescribed as essential qualifications for appointment as professionals in factories/ports as per the statutes, should be recognised by the Apex Body on OSH.

All safety officers, factory medical officers, industrial hygienists appointed/to be appointed in factories and ports should be accredited/registered with the Apex Body on OSH.

The syllabus at college/university levels especially in the areas of science, technology and medicine should be modified to include topics of safety and health. Efforts should be made in medicine field and engineering field to introduce a compulsory subject in field of occupational health and occupational safety with the help of Indian Medical Council/University Grants Commission/All India Council of Technical Education.

Public awareness about health hazards due to environmental pollution, diseases due to exposure to harmful substances should be created through mass media. Booklets, pamphlets, leaflets etc. should be prepared and distributed amongst the industrial/port workers for creating awareness. For this purpose, a component in the proposed plan schemes for the Xth Plan should also be included, seeking cooperation/participation of organizations specialized in the field of safety, health and environment.

A short-term course (15 – 30 days) should be designed and conducted for the medical doctors in government, semi-government, ESI hospitals for increasing their awareness and competence in diagnosis of occupational diseases. This will also enable them to report the suspected cases of occupational disease to authorities concerned in time.

Regular training programmes on occupational health including the Certificate Course on Industrial Medicine should also be conducted at Regional Labour Institutes under DGFASLI.

In order to strengthen the OSH education and training and improving their quality and complete compliance with the spirit of the provisions of the Factories Act which place duties of the Occupier for providing suitable training to their workers and supervisors, there is need for development of Model Guidelines for Approval of Training Centres/Institutes by CIFs as required under Section 111-A of the Factories Act, Development of Model Curriculae and Manuals of Training Courses for key categories of workers (such as those employed in hazardous processes and dangerous operations) and Development of Educational Modules on OSH for inclusion in the syllabi of the Engineering colleges.

3.5.4 Consultancy studies and services

Institutions and professionals rendering consultancy services in the field of occupational safety and health should be recognised at national level by Apex Body or any other agency made responsible for that purpose.

Private laboratories, or laboratories attached to technical institutions should be encouraged to undertake consultancy services in the field of workplace environment monitoring, health monitoring etc. These laboratories should be registered/accredited by the Apex Body or any other agency appointed by Apex Body for that purpose.

Existing facilities at CLI, RLIs, NIOH, ITRC should be upgraded to the level of National Referral Laboratories.

3.5.6 Participation of NGO/other organisation in activities of DGFASLI

For undertaking national level studies and surveys, DGFASLI should seek cooperation in the form of facilities, manpower and financial resources from employers organizations/associations.

National level workshops, seminars and specialized training progammes should be conducted in collaboration with NGOs and professional organizations such as NSC, LPA, OISD, BIS etc.

Local level awareness programmes and promotional programmes should also be arranged by DGFASLI for spreading the safety and health message amongst general population. This should be done in collaboration with local level community bodies/industries, association/NGOs.

3.5.7 State Inspectorates of Factories

In order to bring in the uniformity and to strengthen the status of Chief Inspector of Factories for making decisions in matters of safety and health, the Chief Inspector of Factories should be selected from amongst the cadre of Inspectors of Factories. He should be given the status of the Head of Department in the state.

The system of appointing medical practitioners particularly those working in either government/government aided hospitals or even private practitioners as certifying surgeons for carrying out the activities as envisaged under the provisions of the Factories Act should also be adopted by states. However, nominated certifying surgeons should be adequately trained in the field of occupational health.

All officers of Inspectorates of Factories at local level and regional level should be provided with basic infrastructure such as Cellular Telephone, Residence telephone, computer, fax and transport. Networking of local and regional officers should also be established for easy and quick transfer of information from one office to another.

Online submission of statutory forms, compliance reports and other statutory information by occupiers of the factory should be facilitated. For online dissemination of information regarding new developments, circulars, directives and changes in rules and regulations, these information should be placed on the web-site of the inspectorates of factories.