| Furnishing against risk |

| Sayantani Kar / Mumbai February 9, 2010, 0:44 IST |

|

|

Toy maker Hanung’s move to hedge risks by diversifying into furnishings has started to pay off.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

The economic slowdown in the West has been bad news for Indian exporters. Orders have become hard to get, and prices are under squeeze. In this bleak scenario, Hanung Toys & Textiles, India’s largest soft toy maker and exporter, has got an order worth $100 million for home furnishings. For competitive reasons, Chairman & Managing Director Ashok Kumar Bansal is reluctant to give the name of the customer, though he discloses it is located in the United States. More important, the order, which was placed in January 2010, has taken Hanung’s order book size to $328 million (around Rs 1,500 crore), of which two-thirds is home furnishing. The furnishings will be shipped over three years, and will begin to show in the company’s revenues as early as the first quarter of 2010-11.

The economic slowdown in the West has been bad news for Indian exporters. Orders have become hard to get, and prices are under squeeze. In this bleak scenario, Hanung Toys & Textiles, India’s largest soft toy maker and exporter, has got an order worth $100 million for home furnishings. For competitive reasons, Chairman & Managing Director Ashok Kumar Bansal is reluctant to give the name of the customer, though he discloses it is located in the United States. More important, the order, which was placed in January 2010, has taken Hanung’s order book size to $328 million (around Rs 1,500 crore), of which two-thirds is home furnishing. The furnishings will be shipped over three years, and will begin to show in the company’s revenues as early as the first quarter of 2010-11.

Hanung badly needed a booster dose. The downturn had set it back by a few years. Its target to bring in sales of Rs 1,000 crore by 2009-10 is unlikely to happen. Neither did talks with a Chinese company for acquisition work out. Plans to open more of its own stores in India got stalled. Profit (before tax) fell 3 per cent in 2008-09 to Rs 74 crore. If there is a revival in the fortunes of the company, Bansal can thank his stars for the foray into home furnishings way back in 2003.

It was a move to hedge the risks. If the toy market ran into rough weather — there are, after all, no entry barriers in the business; Hanung has no patented technology that others cannot replicate — furnishings could provide relief. But the kind of toys Hanung makes sell at higher profit margins than furnishings because these are value-added products. The idea for the diversification was not Bansal’s; it was suggested by the company’s toy customers who also shopped for home furnishing in India.

Winning move

For Bansal, the diversification was not a huge challenge. Furnishings required skill sets not very different to toys, though the manual labour was less. Once investments in machines were made, it meant a less exacting production process than toys. “Home furnishings are two-dimensional products and do not have to be as perfect as three-dimensional toys,” says Bansal. This new line of business brought in steadier volumes, albeit at lesser profit margins than toys. Home furnishings now bring in 60 per cent of Hanung’s sale, and Bansal says growth is 30 per cent.

In the last seven years, Hanung has signed 15 customers abroad for furnishings, apart from the five who source both toys and home furnishing such as bed linen from the company. Some customers for home furnishing have ended up buying soft toys from Hanung as well; to match the themed bed linen, for example. As a result, while other textile exporters are straddled with idle machines in their factories, Hanung’s toy factories are running at full steam and its furnishing plants are slated to hit 100 per cent capacity, claims Bansal. Raw materials have been booked and the production plan is ready.

Hanung banks on two traits — its low cost of operations and its value additions — which together help it get better profit margins from customers than rivals. The profit margin in the new order, reckons Bansal, could be as high as 20 per cent, which is healthier than the average 17 per cent in home furnishings. Product designs such as faux embroidery and patchwork have helped differentiate its products. Hanung’s team of 40 in-house designers creates prototypes based on customer specifications. Value additions in design let Hanung differentiate its toys as well, enabling it to land orders such as the Rs 600-crore, four-year one from Ikea, the Swedish lifestyle retailer.

Customer satisfaction

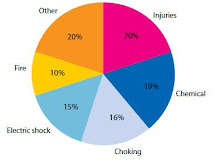

Bansal also works on softer aspects like social compliances, service and safety measures to convince customers: “This is why it often takes a tour of our factories to help new customers make up their mind,” says he. The company discloses all safety measures such as stringent checks from procurement of raw materials till the end of production. Checks are carried out for missing threads, on strength of seams and colour longevity during cutting and sewing and for metal detection to weed out any stray needle. Non-toxic fibres and dyes have also set it notches above Chinese toys which have drawn flak for being toxic.

To fend off suppliers from China, Pakistan and nations close to the US such as Mexico and Brazil, Hanung concentrates on using better fabrics with higher thread counts, while reining in other input costs. Its factories are based in special economic zones (for duty-free import of raw materials) and states with tax holidays such as Uttarakhand. Dyed water is treated for reuse, while backward integration in its plants for fabric weaving leads to a saving of 2 to 3 per cent and cuts down lead times. Bansal optimises the production costs by using 180 grams per square metre cloth for the US market and 200 grams per square metre for the UK market, which with little intelligible difference in quality still makes for a 5 per cent difference in pricing for the customers. Consumers in the US tend to buy furnishings more often and hence prices need to be low, while European consumers change their furnishings less and shell out more for their buys. Still, the downturn has taken its toll. Bansal admits that he has had to accept lower prices, but it has helped him retain his customers.

Domestic business

Despite 40 different customers across five continents, Hanung does not want to lose sight of its home market. An investment analyst says, “It is important to increase its domestic presence, because at the end of the day customer sentiments in other countries are beyond us, while in India the insights are easy to come.” There is the ever-present threat of a Chinese influx, similar to the one that swept the Indian toy industry 1993-onwards and took away nearly 80 per cent of the domestic market, putting Indian toymakers out of business. However, Bansal insists, “Chinese toys sell for much less. We are in the premium segment because of the enhancements we make to regular products such as a teddy bear.”

Hanung’s toy labels, Muskaan and Play-n-Pets, and furnishing label Splash retail through modern trade chains such as Lifestyle, Pyramid and Pantaloons, apart from the company’s own stores which are scattered in the north. Distributors take its products to stores in high streets. In the US, Hanung’s toys sell for an average of $15 to $20 and home furnishing products like bed linen for $100, while in India its toys sell for Rs 300 and bed linen for Rs 2,000. Latching on to the appeal of indigenous animated movies, the company’s licensing of Hanuman from Percept Pictures is still going strong. Bansal expects the expansion of the toy capacity by 10 million pieces would let Hanung reach 500 more stores by the end of 2010.

Though it does not plan to advertise in mass media, the growing fear of toxic toys might help Hanung establish a stronger brand recall. A parent claims in a blog, “I am now concerned about the quality of toys which my child plays with...I check the manufacturer before buying a toy and don’t buy Chinese toys anymore. But Hanung’s Play-n-Pets and Muskaan are definitely on my list.” Even if India lifts the ban on Chinese toys that don’t meet international safety standards, Hanung just might stay its ground in a market that is growing at 30 per cent.

SOURCE

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment