Is It Time to Retrain B-Schools?

Harvard Business School, on the Charles River. Its dean wants more focus on managing risk.

JOHN Thain has one. So do Richard Fuld, Stanley O’Neal andVikram Pandit. For that matter, so does John Paulson, the hedge fund kingpin.

Readers' Comments

Readers shared their thoughts on this article.

Yes, all five have fat bank accounts, even now, and all have made their share of headlines. But these current and former giants of finance also are all card-carrying M.B.A.’s.

The master’s of business administration, a gateway credential throughout corporate America, is especially coveted on Wall Street; in recent years, top business schools have routinely sent more than 40 percent of their graduates into the world of finance.

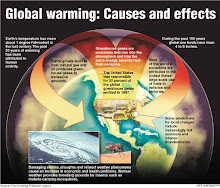

But with the economy in disarray and so many financial firms in free fall, analysts, and even educators themselves, are wondering if the way business students are taught may have contributed to the most serious economic crisis in decades.

“It is so obvious that something big has failed,” said Ángel Cabrera, dean of the Thunderbird School of Global Management in Glendale, Ariz. “We can look the other way, but come on. The C.E.O.’s of those companies, those are people we used to brag about. We cannot say, ‘Well, it wasn’t our fault’ when there is such a systemic, widespread failure of leadership.”

Critics of business education have many complaints. Some say the schools have become too scientific, too detached from real-world issues. Others say students are taught to come up with hasty solutions to complicated problems. Another group contends that schools give students a limited and distorted view of their role — that they graduate with a focus on maximizing shareholder value and only a limited understanding of ethical and social considerations essential to business leadership.

Such shortcomings may have left business school graduates inadequately prepared to make the decisions that, taken together, might have helped mitigate the financial crisis, critics say.

“There are extraordinary things taking place in business education, and a lot that is very promising,” said Judith F. Samuelson, executive director of the Business and Society Program at the Aspen Institute. “But what’s the central theorem of business education? It’s wanting.”

Some employers and recruiters also question the value of an M.B.A., and are telling young people they can get better training on the job than in business school. A growing number are setting up programs to help employees develop skills in-house.

On many campuses, changes are under way in courses and curriculums. Some schools are heightening their focus on long-term thinking or leadership, and many are adding seminars to address the economic crisis.

Jay O. Light, the dean of Harvard Business School, argues that there have been imbalances both on campuses and in the economy. “We lived through an enormous extended period of financial good times, and people became less focused on risks and risk management and more focused on making money,” he said. “We need to move that focus back toward the center.”

BUSINESS SCHOOLS have looked inward before, and some of the current problems may have stemmed from their last major self-examination. In the late 1950s, reports that the Ford and Carnegie foundations commissioned found mediocre faculty, and curriculums narrowly focused on vocational skills.

One of their recommendations was for business schools to become much more analytical and rigorous in their approach. And, over the years, that happened almost everywhere. Doctoral programs are commonplace. Professors conduct independent research and publish often in scholarly journals. Students learn complex models for analyzing competitive strategy, valuing options and more.

But schools may have gone too far in this direction, according to Warren Bennis, a professor of management at the University of Southern California. The schools suffer from “an overemphasis on the rigor and an underemphasis on relevance,” he said. “Business schools have forgotten that they are a professional school.”

Henry Mintzberg, a professor of management studies at McGill University in Montreal, also argues that because students spend so much time developing quick responses to packaged versions of business problems, they do not learn enough about real-world experiences.

For all of the emphasis on analytical rigor in business schools today, another major recommendation of the foundations’ reports from the 1950s — that business become a true profession, with a code of conduct and an ideology about its role in society — got far less traction, said Rakesh Khurana, a professor at Harvard Business School and author of “From Higher Aims to Hired Hands,” a historical analysis of business education.

SOURCE

: John Thain has one. So do Richard Fuld, Stanley O’Neal and Vikram Pandit. So does John Paulson, the hedge fund kingpin. Yes, all five have fat bank accounts, and all have made their share of headlines. But these current and former giants of finance are all card-carrying MBAs.

The master of business administration, a gateway credential throughout corporate America, is coveted on Wall Street; in recent years, top business schools have routinely sent more than 40% of their graduates into the world of finance.

But with the economy in disarray and so many financial firms in free fall, analysts, and even educators themselves, are wondering if the way business students are taught may have contributed to the most serious economic crisis in decades.

“It is so obvious that something big has failed,” said Angel Cabrera, dean of the Thunderbird School of Global Management in Glendale, Arizona. “We can look the other way, but come on. The CEOs of those com-panies, those are people we used to brag about. We cannot say, ‘Well, it wasn’t our fault’ when there is such a systemic, widespread failure of leadership.”

Critics of business education have many complaints. Some say the schools have become too scientific, too detached from real-world issues. Others say students are taught to come up with hasty solutions to complicated problems. Another group contends that schools give students a limited and distorted view of their role — that they graduate with a focus on maximising shareholder value and only a limited understanding of ethical and social considerations essential to business leadership.

Such shortcomings may have left business school graduates inadequately prepared to make the decisions that, taken together, might have helped mitigate the financial crisis, critics say.

“There are extraordinary things taking place in business education, and a lot that is very promising,” said Judith F Samuelson, executive director of the Business and Society Programme, the Aspen Institute. “But what’s the central theorem of business education? It’s wanting.” Some employers and recruiters also question the value of an MBA, and are telling young people they can get better training on the job than in business school. A growing number are setting up programmes to help employees develop skills in-house.

On many campuses, changes are under way in courses and curriculum. Some schools are heightening their focus on long-term thinking or leadership, and many are adding seminars to address the economic crisis.

Jay O Light, the dean of...

Single Page Format 1 - 2 - 3 - Next

Exec Integral Leadership

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment