Friday, November 21, 2008

How Blackouts happen

by Marshall Brain

More Science Videos »

The blackout on August 14, 2003 was the biggest in U.S. history. And just like every major blackout, it raised a lot of questions about how our power distribution system works.

At a high level, the power grid is a very simple thing.

It consists of a set of large power plants (hydropower plants, nuclear power plants, etc.) all connected together by wires. One grid can be as big as half of the United States. (See How Power Distribution Grids Work to learn about the different pieces of the grid.)

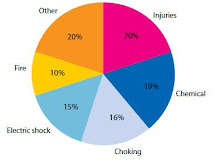

Photo courtesy U.S. Department of EnergyA breakdown of the major power plants inthe United States, by type

A grid works very well as a power distribution system because it allows a lot of sharing. If a power company needs to take a power plant or a transmission tower off line for maintenance, the other parts of the grid can pick up the slack.

The thing that is so amazing about the power grid is that it cannot store any power anywhere in the system. At any moment, you have millions of customers consuming megawatts of power. At that same moment you have dozens of power plants producing exactly the right amount of power to satisfy all of that demand. And you have all the transmission and distribution lines sending the power from the power plants to the consumers.

Photo courtesy U.S. Department of EnergyA map of U.S. electric control area operators (CAO). Computerized systems at each CAO monitor the power grid activity and balance power generation (supply) with power consumption (demand).

This system works great, and it can be highly reliable for years at a time. However, there can be times, particularly when there is high demand, that the interconnected nature of the grid makes the entire system vulnerable to collapse.

Here's how that happens:

Let's say that the grid is running pretty close to its maximum capacity. Something causes a power plant to suddenly trip off line. The "something" might be anything from a serious lightning strike to a bearing failure and subsequent fire in a generator.

When that plant disconnects from the grid, the other plants connected to it have to spin up to meet the demand. If they are all near their maximum capacity, then they cannot handle the extra load. To prevent themselves from overloading and failing, they will disconnect from the grid as well. That only makes the problem worse, and dozens of plants eventually disconnect.

That leaves millions of people without power.

The same thing can happen if a big transmission line fails. In 1996 there was a major blackout in the western U.S. and Canada because the wires of a major transmission line sagged into some trees and shorted out. When that transmission line failed, all of its load shifted to neighboring transmission lines. They then overloaded and failed, and the overload cascaded through the grid.

In nearly every major blackout, the situation is the same. One piece of the system fails, then the pieces near it cannot handle the increased load caused by the failure, so they fail. The multiple failures make the problem worse and worse and a large area ends up in the dark.

One solution to the problem would be to build significant amounts of excess capacity -- extra power plants, extra transmission lines, etc. By having extra capacity, it would be able to pick up the load at the moment that something else failed. That approach would work, but it would increase our power bills.

At this moment we have made the choice as a society to save the money and live with the risk of blackouts. Once we get tired of blackouts and the disruption they cause, we will make a different choice.

How Power Distribution Grids Work

How Hydropower Plants Work

How Nuclear Power Works

How Fuel Cells Work

How Circuit Breakers Work

Why does the phone still work when the power goes out?

-->

Big Blackouts in U.S. History

The Great Northeast Blackout of 1965: After a relay failure, more than 80,000 square miles of the northeastern United States and parts of Canada lost power, turning the lights out on 30 million people.

The New York Blackout of 1977: One hot night in July, multiple lightning strikes knocked out power to the entire city of New York, leaving 8 million people without light or air conditioning. The blackout triggered mass looting and arson across much of the city.

The Northwestern Blackout of 1996: Transmission lines sagged into some trees, causing an electrical short that knocked out power to more than 4 million people in Oregon, California and other western states.

The Blackout of 2003:Cities across the midwestern United States, northeastern United States and southern Canada lost power, apparently due to a problem with a series of transmission lines known as "The Lake Eerie Loop." Roughly 50 million people lost power.

Howstuffworks

Electrical Contractors

Electric Power Plants

WWW Howstuffworks com

How Stuff Works com

Explanations

How Power Grids Work

How Hydropower Plants Work

How Circuit Breakers Work

more

The price of change [electricity supply industry deregulation]Wollenberg, B.F.Potentials, IEEEVolume 16, Issue 5, Dec 1997/Jan 1998 Page(s):14 - 16Digital Object Identifier 10.1109/45.645825Summary:The electric utilities in the USA are being deregulated by government order. Not all of the details have been worked out at this time, but some of the strengths and weaknesses are beginning to show. Unlike countries where government agencies owned and operated electric power systems and deregulation meant privatization, the US electric systems are predominantly private. They must be reorganized for deregulation. One difficulty comes from the fact that many separately owned and managed transmission systems must work together. Issues of reliability and responsibility for service provided by the transmission systems are not completely clear. Another issue is the separation of generation from transmission in companies where these functions were traditionally owned and managed together. The final test of whether deregulation of the US electric utilities is successful will be the perception of the population. These issues are discussed by the author in this paper» View citation and abstract

more

Shrieking in Cyberspace

Relax. Your computer’s fine. We’re only blowing billions on an overhyped terror threat.

Winn Schwartau was standing in the shower of his suburban Nashville home one morning 13 years ago when he was visited, he says, by a vision. It was a vision of the future, a vivid and terrifying image of a high-tech apocalypse.

He saw terrorists with keyboards, unleashing swarms of computer viruses into cyberspace. He saw gangs of foreign mercenaries hacking computerized banking systems and tipping the Western economic system into chaos. He saw religious fanatics gaining access to electric power grids and triggering mass blackouts. He saw sewage treatment plants overflowing, life support machines sputtering, bridges falling, planes crashing.

“I just closed my eyes and this whole movie played out in my mind,” he says. “I counted up all the threat-based capabilities out there and glued them together. They added up to a nightmare.”

A former rock-and-roll producer with a bushy black mustache, Schwartau took up computers in the early 80s as a “quaint hobby” and went on to start a successful Virginia computer security company. But after his near-religious experience, Schwartau became a full-time dark prophet of the digital age, joining a growing legion of computer engineers, think tankers, academics, novelists and spies convinced that America was headed for what Schwartau called “an electronic Pearl Harbor.”

September 11 instantly recast the threat from a sci-fi pipedream into what the Bush Administration is treating as a grim probability.

Today, so-called cyberterrorism is a top priority of the new Homeland Security Department, the focus of a new FBI division and the rallying cry for a booming new cybersecurity industry. Scenarios vary, but this is the basic premise: Evildoers halfway around the world hack into command and control computer networks here that control dams, factories, hospitals, power plants, air traffic control systems -- even amusement parks. To prevent such attacks, the federal government will spend $4.5 billion next year securing government computers, with private industry shelling out $13.6 billion to build up digital defenses.

It’s easy to forget one simple fact: Cyberterrorism is imaginary. It has never happened. In the 13 years since Schwartau warned of an impending electronic catastrophe, not one single computer attack has been traced to a terrorist organization. The FBI, which now has some 1,000 dedicated “cyber-investigators,” has never responded to a hack, virus or even a spam e-mail linked to a terrorist. What’s more, cyberterrorism may not even be possible – some computer experts say networked computers simply aren’t capable of triggering the sorts of destruction described by cyberterror buffs.

That doesn’t mean terrorists don’t use computers, or that the Internet hasn’t been a boon to thieves, pranksters, disgruntled workers and political activists. But computer crime is not cyberterrorism. And so far anyway, our most dangerous and determined enemies -- al Qaeda or any of the 27 covert groups listed by the federal government as terrorist organizations -- appear only dimly aware of the arcane tricks of computer warfare that inspire such fever dreams in American computer geeks and policy wonks. The scant evidence that the sky is indeed falling – heavy Web traffic from Indonesia, research on electronic switching systems on al Qaeda laptops, rumors of master hackers at Camp X Ray in Cuba – might get pulses racing among fans of Tom Clancy. But it’s hard to come away from any sober reality check without concluding that computers are less weapons of mass destruction than weapons of mass annoyance.

While popular scenarios are certainly cinematic – cut to: Matthew Broderick bringing the U.S. to the brink of nuclear war in War Games – the fact is that computers are a lot less connected or all-powerful as we might think. For one thing, most computer systems that control so-called critical infrastructures aren’t even plugged into the Internet. “There seems to be this perception you can log on to America Online, and if you know the right passwords, hack into the national power grid,” says Douglas Thomas, a USC professor and author of two books on hacking and the policing of cyberspace. “People don’t seem to realize that these aren’t publicly accessible systems. Why would they be? Most sensitive military and government networks are completely shielded. A terrorist would have to be a ranking official in the military to get access to these networks – and if that’s happening, we’ve got way bigger problems than computer security to worry about.”

More importantly, most critical computer systems are vast labyrinths of code that can’t be navigated with the help of store-bought manuals. As one former hacker recruited by Cisco Systems as a security architect confided, “I’ve worked here two years and if someone came along and asked me where the source code is for the operating system, I’d have no idea.”

But perhaps the main reason why cyberterrorism has remained more fiction than fact is that we Americans know more – and care more – about computers than any of our enemies. While most Westerners have trouble even remembering a time before e-mail, ATMs or cell phones, technology figures a lot less prominently in the lives of, say, the average Islamic fundamentalist. And so far anyway, low-tech tools like bombs, bullets and box cutters have proven to be highly effective instruments for whipping up terror.

What’s really going on then, suggests author Robert Young Pelton, is the latest outbreak of the techno-jitters that brought us Y2K hysteria -- this time charged with the lingering shock of Sept. 11. With a surplus of fear and a shortage of anything we can actually see, we’ve fused two of the most mysterious and incomprehensible forces of the modern age: technology and terrorism. It’s the Red Scare of the information age, complete with invisible enemies, doomsdays and massive government contracts.

“The whole idea plays to our deepest fears,” says Pelton, whose unauthorized trips into combat zones led to the first interview with the famed “American Taliban,” John Walker Lindh. “Terrorists just don’t have the same mindset. What you’re really looking at is a big fat government trying to reshape the enemy in its own form.”

•••

To hear Senator John Edwards tell it, cyberterrorism is a national emergency that should stir the resolve of every American. “We live in a world where a terrorist can do as much damage with a keyboard and a modem as with a gun or a bomb,” the North Carolina Democrat declared in January. Just a month earlier, Congress targeted cyberterrorists as part of the U.S.A. Patriot Act, giving police sweeping new surveillance powers and stiffening sentences for those convicted of computer crime.

It’s unlikely that any of these tough new laws will make a whit of difference in the fight against terrorism. Where they’ve already come into play is in the prosecution of teenage hackers who’ve expressed half-baked political motives, or in efforts to curtail online fraud, extortion, corporate espionage and other economic crimes, which cost U.S. industry upward of $15 billion in 2001 alone.

Leading the government’s counter-offensive is Richard E. Clarke, the nation’s first cybersecurity czar.

A former national security advisor who has worked for every president since Reagan, Clarke is bald, jowly and authoritative, a towering presence among the nerdy code jockeys and slick consultants who make up much of the info-war camp. Since his appointment, he’s criss-crossed the country spreading the gospel of digital vigilance, rallying crowds of IT worker bees with hawkish quotes from Churchill and dire warnings that our enemies are poised to “attack us not with missiles and bombs but with bits and bytes.”

Lounging in a hotel lobby during a recent stop in Portland, Clarke is quick to acknowledge that neither he nor anyone in the 13 agencies and offices of the U.S. intelligence community has any evidence that terrorists are now using computers as weapons. “We haven’t seen an attack by a terrorist group meant to hack its way into a Web site or otherwise do damage,” he says. “We haven’t seen the Palestinians turn off the electricity in Haifa.

We haven’t yet seen a terrorist group drop the electric power grid, crash a communications network or disrupt a banking system.”

But just because they haven’t yet doesn’t mean they won’t. Clarke doesn’t discount any of the cyberterror possibilities, quickly ticking off a few that he finds the most plausible: an attack on the military networks that control troop deployment, or a hack of the computer routers that control the Internet itself. In another favorite plot, a mysterious outbreak of anthrax is followed by a computer attack on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, slowing down response teams and multiplying the body count.

Of course no one, not even the Patton-like Clarke, can say for certain whether such events will ever come to pass, or how to measure their probability against other post-Sept. 11 threats, from truck bombs on the Bay Bridge to anthrax-filled crop dusters over Manhattan. The only real evidence that terrorists are even aware of the destructive capabilities of computers emerged this summer, with a report in The Washington Post that al Qaeda laptops seized in Afghanistan contained research about digital devices that allow remote computers to do things like throw railway switches and adjust the flow of oil and water.

Clarke admits the public evidence is limited but claims that classified intelligence indicates that terrorists are poised to strike. Clarke is meanwhile rallying a whole new wing of government to fight back. On that early summer evening in Portland, Clarke retreated to his hotel suite, switched on CNN and watched his boss announce to the nation plans to create a permanent White House Department of Homeland Security. Among the new department’s responsibilities is the protection of cyberspace, adding some 150,000 federal agents and an annual budget of $37 billion to the potential war chest. His nose buried in a stack of reports on the new bureaucracy, Clarke couldn’t conceal a grin.

“This is big,” he said. “Very, very big.”

•••

While cyberterror is certainly scary, a close look at the cases cited as proof of the threat is much less sensational. Typical was a December 2001 news item that many pronounced to be the long predicted first shot of the info-war. According to an Indian newspaper report, Islamic militants had gone undercover at Microsoft and planted a so-called Trojan horse virus in the new Windows XP operating system.

Fortunately, the whole story was bogus. “It was a bizarre allegation that had no basis in fact,” says Microsoft spokesman Jim Desler. Still, the tale demonstrates a crucial point in the hype over cyberterrorism. Can anyone seriously count a computer virus that crashes a hard drive in the same category as a radiological bomb that craters a city?

The important difference, of course, is violence. Terrorism simply isn’t such a big deal without explosions, dismemberment or death. And notwithstanding the killer cyborgs in Terminator or the merciless HAL in 2001, computers don’t have much talent for killing people. Most authorities – including the government’s National Infrastructure Protection Center – make this distinction, defining a cyberterrorist attack as a politically motivated, computer assault on civilians that causes physical harm.

This is bad news for cyberterror buffs, because it eliminates from discussion 99 percent of the cases cited as proof that cyberterrorism is a clear and present danger. There’s simply not much blood and guts in the hacker users manual. There are, however, a multitude of methods for screwing up another computer, slowing down a Web site or stealing private files.

After the standoff between China and U.S. over a downed spy plane two years ago, the home pages of the White House, the Air Force and another 1,200 American Web sites were hacked, many tagged with political slogans. Such Web defacements have become routine in Israel, where pro-Palestinian hackers have declared a “cyber jihad” and Israelis have organized a “cyber militia” whose handiwork includes the sudden appearance of porn on the homepage of those fun-loving hedonists, Hamas.

More damaging are so-called denial of service attacks, previously employed to clog NATO servers following the U.S. bombing of Serbia. John Arquilla, a leading Pentagon theorist and professor of public policy at Pepperdine, sounds like he’s analyzing an invasion of undead flesh eaters and mighty warriors when he describes “master hackers” and their power to amass enormous arsenals of zombies.” But USC’s Thomas wonders whether terrorists get so worked up over what is essentially a nasty trick for freezing Web sites and disrupting e-mail. “I just can’t imagine some lieutenant going back to Osama bin Laden and saying ‘We’ve struck terror in people’s hearts – Yahoo! was inaccessible for over an hour,’” he says.

By far the most damaging form of computer attack is the total takeover, in which a hacker hops over firewalls, puzzles out passwords and gains complete control of a system. It’s called “breaking root,” and it’s the brass ring of hacking. Break root, the theory goes, and you can do anything a computer can: fluctuate the value of the U.S. dollar, stop traffic in midtown Manhattan or redirect all 911-calls to a single pizza parlor.

Breaking root is the basis of all the scarier cyberterror stories, from the global meltdown of Tom Clancy’s Net Force series to the recent FBI reports that al Qaeda hackers may be learning about the digital devices commonly used in American network systems. While total takeover sounds alarming, computer experts say it’s really not such a catastrophic event. In fact, it happens all the time. The CERT Coordination Center, a government-supported computer emergency response team at Carnegie Mellon University, logged some 52,658 security breaches and attacks in 2001.

Experts say between a quarter and a half of those involved a hacker gaining total control of a system. Do the math and you find that in one year, hackers went for more than 13,150 joy rides – and those are just the ones that freaked out their owners enough to call in government computer cops.

“It’s one thing hacking in – it’s another thing entirely operating one of these systems,” says Erik Ginorio, a former hacker and FBI informant from San Francisco who now works in private security. “To do real damage or make a system do something the owner doesn’t want done, you need real experience on high-end stuff. You need equipment and tons and tons of knowledge about the systems we’re running. And there’s just not that much of that high-end equipment floating around out there.”

•••

Cyberterrorism may be hypothetical, but there’s nothing hypothetical about the billions of dollars flooding into the cybersecurity industry. In fact, cyberterrorism may be the best thing to happen to the tech sector since Y2K hysteria -- except this boom has no built-in expiration date. According to Forrester Research, U.S. businesses spent $5.7 billion protecting computer data the year before the attacks on the World Trade Center.

Next year they’ll shell out an estimated $13.6 billion, with projections climbing every year through 2006.

EDS, the tech giant founded by Ross Perot, is currently building what is billed as an “unhackable” private Internet for the Navy and Marine Corps at a cost of more than $6 billion. Meanwhile sales of antivirus, intrusion detection and other security software have skyrocketed, and computer geeks are recasting themselves as Chief Security Officers, a new executive level post that that can fetch salaries of $400,000. Even the CIA is hitching a car to the money train, establishing a venture capital firm called In-Q-Tell (named after the James Bond sidekick) to partner with companies developing, among other things, anti-cyberterror technology.

Lower down the food chain are the thousands of consultants, analysts and educators who make their living warning of the dangers lurking inside our laptops. “I caught the wave,” says Matt Devoe, a computer engineer from Washington DC who got into the business at the tender age of 21 after writing his thesis on info-war. He hit the speaking circuit before graduating, got a consulting gig with the Department of Defense and now runs a “multimillion dollar research analysis company” called Technical Defense Incorporated. “It was just starting when I got started and it’s grown ever since.”

Devoe can provoke jitters in the most hardened CEO describing his experiences as a “white hat” hacker hired to attack computer networks. He’s hacked public utilities, air traffic control systems and such corporations as Microsoft and Citygroup and he says he routinely finds himself in a position where he could steal vast stores of money or trade secrets or make his presence known to millions of innocent bystanders.

Other experts doubt it’s quite so simple. “If they could’ve, they would’ve,” says George Friedman, a former Pentagon advisor who now runs an Austin-based private intelligence company called Stratfor. Friedman says the legions of cyberterror “experts” are little more than storytellers. “They love technical head games, but ask them to point at really successful attacks on critical infrastructures and they’re at a loss,” he says.

It’s true that there’s nothing cyberterror buffs enjoy more than pointing out vulnerabilities and bragging about how they could exploit them. Howard Schmidt, former security chief at Microsoft and now the deputy chairman of the President's Critical Infrastructure Protection Board, was reminded of this professional pride this summer, when he told an assembly of computer engineers that in all his years in the field, he himself had never been a victim of computer crime. “Is that a challenge?” hollered a consultant in the crowd. “We have the technology.”

The room erupted. And the laughter wasn’t just at the expense of an easy target like Schmidt. It hit on an obvious but rarely-spoken truth: that most of us will never encounter even a petty thief online, but that the creators of the most devilish cyberterror scenarios are right here among us, designing software, writing techno-thrillers, and setting government policy. And they’re scaring us silly.

“We’re all sitting around looking in the mirror, asking if someone was just like us, how would he take advantage of our weaknesses?” says Fred Freer, a retired CIA analyst and specialist in the Middle East. “Of course they’re not just like us. We’ve got to get out of this crazy reactive mode and stop trying to scare ourselves. We’re all chasing our tails and looking more and more foolish.”

more

More Science Videos »

The blackout on August 14, 2003 was the biggest in U.S. history. And just like every major blackout, it raised a lot of questions about how our power distribution system works.

At a high level, the power grid is a very simple thing.

It consists of a set of large power plants (hydropower plants, nuclear power plants, etc.) all connected together by wires. One grid can be as big as half of the United States. (See How Power Distribution Grids Work to learn about the different pieces of the grid.)

Photo courtesy U.S. Department of EnergyA breakdown of the major power plants inthe United States, by type

A grid works very well as a power distribution system because it allows a lot of sharing. If a power company needs to take a power plant or a transmission tower off line for maintenance, the other parts of the grid can pick up the slack.

The thing that is so amazing about the power grid is that it cannot store any power anywhere in the system. At any moment, you have millions of customers consuming megawatts of power. At that same moment you have dozens of power plants producing exactly the right amount of power to satisfy all of that demand. And you have all the transmission and distribution lines sending the power from the power plants to the consumers.

Photo courtesy U.S. Department of EnergyA map of U.S. electric control area operators (CAO). Computerized systems at each CAO monitor the power grid activity and balance power generation (supply) with power consumption (demand).

This system works great, and it can be highly reliable for years at a time. However, there can be times, particularly when there is high demand, that the interconnected nature of the grid makes the entire system vulnerable to collapse.

Here's how that happens:

Let's say that the grid is running pretty close to its maximum capacity. Something causes a power plant to suddenly trip off line. The "something" might be anything from a serious lightning strike to a bearing failure and subsequent fire in a generator.

When that plant disconnects from the grid, the other plants connected to it have to spin up to meet the demand. If they are all near their maximum capacity, then they cannot handle the extra load. To prevent themselves from overloading and failing, they will disconnect from the grid as well. That only makes the problem worse, and dozens of plants eventually disconnect.

That leaves millions of people without power.

The same thing can happen if a big transmission line fails. In 1996 there was a major blackout in the western U.S. and Canada because the wires of a major transmission line sagged into some trees and shorted out. When that transmission line failed, all of its load shifted to neighboring transmission lines. They then overloaded and failed, and the overload cascaded through the grid.

In nearly every major blackout, the situation is the same. One piece of the system fails, then the pieces near it cannot handle the increased load caused by the failure, so they fail. The multiple failures make the problem worse and worse and a large area ends up in the dark.

One solution to the problem would be to build significant amounts of excess capacity -- extra power plants, extra transmission lines, etc. By having extra capacity, it would be able to pick up the load at the moment that something else failed. That approach would work, but it would increase our power bills.

At this moment we have made the choice as a society to save the money and live with the risk of blackouts. Once we get tired of blackouts and the disruption they cause, we will make a different choice.

How Power Distribution Grids Work

How Hydropower Plants Work

How Nuclear Power Works

How Fuel Cells Work

How Circuit Breakers Work

Why does the phone still work when the power goes out?

-->

Big Blackouts in U.S. History

The Great Northeast Blackout of 1965: After a relay failure, more than 80,000 square miles of the northeastern United States and parts of Canada lost power, turning the lights out on 30 million people.

The New York Blackout of 1977: One hot night in July, multiple lightning strikes knocked out power to the entire city of New York, leaving 8 million people without light or air conditioning. The blackout triggered mass looting and arson across much of the city.

The Northwestern Blackout of 1996: Transmission lines sagged into some trees, causing an electrical short that knocked out power to more than 4 million people in Oregon, California and other western states.

The Blackout of 2003:Cities across the midwestern United States, northeastern United States and southern Canada lost power, apparently due to a problem with a series of transmission lines known as "The Lake Eerie Loop." Roughly 50 million people lost power.

Howstuffworks

Electrical Contractors

Electric Power Plants

WWW Howstuffworks com

How Stuff Works com

Explanations

How Power Grids Work

How Hydropower Plants Work

How Circuit Breakers Work

more

The price of change [electricity supply industry deregulation]Wollenberg, B.F.Potentials, IEEEVolume 16, Issue 5, Dec 1997/Jan 1998 Page(s):14 - 16Digital Object Identifier 10.1109/45.645825Summary:The electric utilities in the USA are being deregulated by government order. Not all of the details have been worked out at this time, but some of the strengths and weaknesses are beginning to show. Unlike countries where government agencies owned and operated electric power systems and deregulation meant privatization, the US electric systems are predominantly private. They must be reorganized for deregulation. One difficulty comes from the fact that many separately owned and managed transmission systems must work together. Issues of reliability and responsibility for service provided by the transmission systems are not completely clear. Another issue is the separation of generation from transmission in companies where these functions were traditionally owned and managed together. The final test of whether deregulation of the US electric utilities is successful will be the perception of the population. These issues are discussed by the author in this paper» View citation and abstract

more

Shrieking in Cyberspace

Relax. Your computer’s fine. We’re only blowing billions on an overhyped terror threat.

Winn Schwartau was standing in the shower of his suburban Nashville home one morning 13 years ago when he was visited, he says, by a vision. It was a vision of the future, a vivid and terrifying image of a high-tech apocalypse.

He saw terrorists with keyboards, unleashing swarms of computer viruses into cyberspace. He saw gangs of foreign mercenaries hacking computerized banking systems and tipping the Western economic system into chaos. He saw religious fanatics gaining access to electric power grids and triggering mass blackouts. He saw sewage treatment plants overflowing, life support machines sputtering, bridges falling, planes crashing.

“I just closed my eyes and this whole movie played out in my mind,” he says. “I counted up all the threat-based capabilities out there and glued them together. They added up to a nightmare.”

A former rock-and-roll producer with a bushy black mustache, Schwartau took up computers in the early 80s as a “quaint hobby” and went on to start a successful Virginia computer security company. But after his near-religious experience, Schwartau became a full-time dark prophet of the digital age, joining a growing legion of computer engineers, think tankers, academics, novelists and spies convinced that America was headed for what Schwartau called “an electronic Pearl Harbor.”

September 11 instantly recast the threat from a sci-fi pipedream into what the Bush Administration is treating as a grim probability.

Today, so-called cyberterrorism is a top priority of the new Homeland Security Department, the focus of a new FBI division and the rallying cry for a booming new cybersecurity industry. Scenarios vary, but this is the basic premise: Evildoers halfway around the world hack into command and control computer networks here that control dams, factories, hospitals, power plants, air traffic control systems -- even amusement parks. To prevent such attacks, the federal government will spend $4.5 billion next year securing government computers, with private industry shelling out $13.6 billion to build up digital defenses.

It’s easy to forget one simple fact: Cyberterrorism is imaginary. It has never happened. In the 13 years since Schwartau warned of an impending electronic catastrophe, not one single computer attack has been traced to a terrorist organization. The FBI, which now has some 1,000 dedicated “cyber-investigators,” has never responded to a hack, virus or even a spam e-mail linked to a terrorist. What’s more, cyberterrorism may not even be possible – some computer experts say networked computers simply aren’t capable of triggering the sorts of destruction described by cyberterror buffs.

That doesn’t mean terrorists don’t use computers, or that the Internet hasn’t been a boon to thieves, pranksters, disgruntled workers and political activists. But computer crime is not cyberterrorism. And so far anyway, our most dangerous and determined enemies -- al Qaeda or any of the 27 covert groups listed by the federal government as terrorist organizations -- appear only dimly aware of the arcane tricks of computer warfare that inspire such fever dreams in American computer geeks and policy wonks. The scant evidence that the sky is indeed falling – heavy Web traffic from Indonesia, research on electronic switching systems on al Qaeda laptops, rumors of master hackers at Camp X Ray in Cuba – might get pulses racing among fans of Tom Clancy. But it’s hard to come away from any sober reality check without concluding that computers are less weapons of mass destruction than weapons of mass annoyance.

While popular scenarios are certainly cinematic – cut to: Matthew Broderick bringing the U.S. to the brink of nuclear war in War Games – the fact is that computers are a lot less connected or all-powerful as we might think. For one thing, most computer systems that control so-called critical infrastructures aren’t even plugged into the Internet. “There seems to be this perception you can log on to America Online, and if you know the right passwords, hack into the national power grid,” says Douglas Thomas, a USC professor and author of two books on hacking and the policing of cyberspace. “People don’t seem to realize that these aren’t publicly accessible systems. Why would they be? Most sensitive military and government networks are completely shielded. A terrorist would have to be a ranking official in the military to get access to these networks – and if that’s happening, we’ve got way bigger problems than computer security to worry about.”

More importantly, most critical computer systems are vast labyrinths of code that can’t be navigated with the help of store-bought manuals. As one former hacker recruited by Cisco Systems as a security architect confided, “I’ve worked here two years and if someone came along and asked me where the source code is for the operating system, I’d have no idea.”

But perhaps the main reason why cyberterrorism has remained more fiction than fact is that we Americans know more – and care more – about computers than any of our enemies. While most Westerners have trouble even remembering a time before e-mail, ATMs or cell phones, technology figures a lot less prominently in the lives of, say, the average Islamic fundamentalist. And so far anyway, low-tech tools like bombs, bullets and box cutters have proven to be highly effective instruments for whipping up terror.

What’s really going on then, suggests author Robert Young Pelton, is the latest outbreak of the techno-jitters that brought us Y2K hysteria -- this time charged with the lingering shock of Sept. 11. With a surplus of fear and a shortage of anything we can actually see, we’ve fused two of the most mysterious and incomprehensible forces of the modern age: technology and terrorism. It’s the Red Scare of the information age, complete with invisible enemies, doomsdays and massive government contracts.

“The whole idea plays to our deepest fears,” says Pelton, whose unauthorized trips into combat zones led to the first interview with the famed “American Taliban,” John Walker Lindh. “Terrorists just don’t have the same mindset. What you’re really looking at is a big fat government trying to reshape the enemy in its own form.”

•••

To hear Senator John Edwards tell it, cyberterrorism is a national emergency that should stir the resolve of every American. “We live in a world where a terrorist can do as much damage with a keyboard and a modem as with a gun or a bomb,” the North Carolina Democrat declared in January. Just a month earlier, Congress targeted cyberterrorists as part of the U.S.A. Patriot Act, giving police sweeping new surveillance powers and stiffening sentences for those convicted of computer crime.

It’s unlikely that any of these tough new laws will make a whit of difference in the fight against terrorism. Where they’ve already come into play is in the prosecution of teenage hackers who’ve expressed half-baked political motives, or in efforts to curtail online fraud, extortion, corporate espionage and other economic crimes, which cost U.S. industry upward of $15 billion in 2001 alone.

Leading the government’s counter-offensive is Richard E. Clarke, the nation’s first cybersecurity czar.

A former national security advisor who has worked for every president since Reagan, Clarke is bald, jowly and authoritative, a towering presence among the nerdy code jockeys and slick consultants who make up much of the info-war camp. Since his appointment, he’s criss-crossed the country spreading the gospel of digital vigilance, rallying crowds of IT worker bees with hawkish quotes from Churchill and dire warnings that our enemies are poised to “attack us not with missiles and bombs but with bits and bytes.”

Lounging in a hotel lobby during a recent stop in Portland, Clarke is quick to acknowledge that neither he nor anyone in the 13 agencies and offices of the U.S. intelligence community has any evidence that terrorists are now using computers as weapons. “We haven’t seen an attack by a terrorist group meant to hack its way into a Web site or otherwise do damage,” he says. “We haven’t seen the Palestinians turn off the electricity in Haifa.

We haven’t yet seen a terrorist group drop the electric power grid, crash a communications network or disrupt a banking system.”

But just because they haven’t yet doesn’t mean they won’t. Clarke doesn’t discount any of the cyberterror possibilities, quickly ticking off a few that he finds the most plausible: an attack on the military networks that control troop deployment, or a hack of the computer routers that control the Internet itself. In another favorite plot, a mysterious outbreak of anthrax is followed by a computer attack on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, slowing down response teams and multiplying the body count.

Of course no one, not even the Patton-like Clarke, can say for certain whether such events will ever come to pass, or how to measure their probability against other post-Sept. 11 threats, from truck bombs on the Bay Bridge to anthrax-filled crop dusters over Manhattan. The only real evidence that terrorists are even aware of the destructive capabilities of computers emerged this summer, with a report in The Washington Post that al Qaeda laptops seized in Afghanistan contained research about digital devices that allow remote computers to do things like throw railway switches and adjust the flow of oil and water.

Clarke admits the public evidence is limited but claims that classified intelligence indicates that terrorists are poised to strike. Clarke is meanwhile rallying a whole new wing of government to fight back. On that early summer evening in Portland, Clarke retreated to his hotel suite, switched on CNN and watched his boss announce to the nation plans to create a permanent White House Department of Homeland Security. Among the new department’s responsibilities is the protection of cyberspace, adding some 150,000 federal agents and an annual budget of $37 billion to the potential war chest. His nose buried in a stack of reports on the new bureaucracy, Clarke couldn’t conceal a grin.

“This is big,” he said. “Very, very big.”

•••

While cyberterror is certainly scary, a close look at the cases cited as proof of the threat is much less sensational. Typical was a December 2001 news item that many pronounced to be the long predicted first shot of the info-war. According to an Indian newspaper report, Islamic militants had gone undercover at Microsoft and planted a so-called Trojan horse virus in the new Windows XP operating system.

Fortunately, the whole story was bogus. “It was a bizarre allegation that had no basis in fact,” says Microsoft spokesman Jim Desler. Still, the tale demonstrates a crucial point in the hype over cyberterrorism. Can anyone seriously count a computer virus that crashes a hard drive in the same category as a radiological bomb that craters a city?

The important difference, of course, is violence. Terrorism simply isn’t such a big deal without explosions, dismemberment or death. And notwithstanding the killer cyborgs in Terminator or the merciless HAL in 2001, computers don’t have much talent for killing people. Most authorities – including the government’s National Infrastructure Protection Center – make this distinction, defining a cyberterrorist attack as a politically motivated, computer assault on civilians that causes physical harm.

This is bad news for cyberterror buffs, because it eliminates from discussion 99 percent of the cases cited as proof that cyberterrorism is a clear and present danger. There’s simply not much blood and guts in the hacker users manual. There are, however, a multitude of methods for screwing up another computer, slowing down a Web site or stealing private files.

After the standoff between China and U.S. over a downed spy plane two years ago, the home pages of the White House, the Air Force and another 1,200 American Web sites were hacked, many tagged with political slogans. Such Web defacements have become routine in Israel, where pro-Palestinian hackers have declared a “cyber jihad” and Israelis have organized a “cyber militia” whose handiwork includes the sudden appearance of porn on the homepage of those fun-loving hedonists, Hamas.

More damaging are so-called denial of service attacks, previously employed to clog NATO servers following the U.S. bombing of Serbia. John Arquilla, a leading Pentagon theorist and professor of public policy at Pepperdine, sounds like he’s analyzing an invasion of undead flesh eaters and mighty warriors when he describes “master hackers” and their power to amass enormous arsenals of zombies.” But USC’s Thomas wonders whether terrorists get so worked up over what is essentially a nasty trick for freezing Web sites and disrupting e-mail. “I just can’t imagine some lieutenant going back to Osama bin Laden and saying ‘We’ve struck terror in people’s hearts – Yahoo! was inaccessible for over an hour,’” he says.

By far the most damaging form of computer attack is the total takeover, in which a hacker hops over firewalls, puzzles out passwords and gains complete control of a system. It’s called “breaking root,” and it’s the brass ring of hacking. Break root, the theory goes, and you can do anything a computer can: fluctuate the value of the U.S. dollar, stop traffic in midtown Manhattan or redirect all 911-calls to a single pizza parlor.

Breaking root is the basis of all the scarier cyberterror stories, from the global meltdown of Tom Clancy’s Net Force series to the recent FBI reports that al Qaeda hackers may be learning about the digital devices commonly used in American network systems. While total takeover sounds alarming, computer experts say it’s really not such a catastrophic event. In fact, it happens all the time. The CERT Coordination Center, a government-supported computer emergency response team at Carnegie Mellon University, logged some 52,658 security breaches and attacks in 2001.

Experts say between a quarter and a half of those involved a hacker gaining total control of a system. Do the math and you find that in one year, hackers went for more than 13,150 joy rides – and those are just the ones that freaked out their owners enough to call in government computer cops.

“It’s one thing hacking in – it’s another thing entirely operating one of these systems,” says Erik Ginorio, a former hacker and FBI informant from San Francisco who now works in private security. “To do real damage or make a system do something the owner doesn’t want done, you need real experience on high-end stuff. You need equipment and tons and tons of knowledge about the systems we’re running. And there’s just not that much of that high-end equipment floating around out there.”

•••

Cyberterrorism may be hypothetical, but there’s nothing hypothetical about the billions of dollars flooding into the cybersecurity industry. In fact, cyberterrorism may be the best thing to happen to the tech sector since Y2K hysteria -- except this boom has no built-in expiration date. According to Forrester Research, U.S. businesses spent $5.7 billion protecting computer data the year before the attacks on the World Trade Center.

Next year they’ll shell out an estimated $13.6 billion, with projections climbing every year through 2006.

EDS, the tech giant founded by Ross Perot, is currently building what is billed as an “unhackable” private Internet for the Navy and Marine Corps at a cost of more than $6 billion. Meanwhile sales of antivirus, intrusion detection and other security software have skyrocketed, and computer geeks are recasting themselves as Chief Security Officers, a new executive level post that that can fetch salaries of $400,000. Even the CIA is hitching a car to the money train, establishing a venture capital firm called In-Q-Tell (named after the James Bond sidekick) to partner with companies developing, among other things, anti-cyberterror technology.

Lower down the food chain are the thousands of consultants, analysts and educators who make their living warning of the dangers lurking inside our laptops. “I caught the wave,” says Matt Devoe, a computer engineer from Washington DC who got into the business at the tender age of 21 after writing his thesis on info-war. He hit the speaking circuit before graduating, got a consulting gig with the Department of Defense and now runs a “multimillion dollar research analysis company” called Technical Defense Incorporated. “It was just starting when I got started and it’s grown ever since.”

Devoe can provoke jitters in the most hardened CEO describing his experiences as a “white hat” hacker hired to attack computer networks. He’s hacked public utilities, air traffic control systems and such corporations as Microsoft and Citygroup and he says he routinely finds himself in a position where he could steal vast stores of money or trade secrets or make his presence known to millions of innocent bystanders.

Other experts doubt it’s quite so simple. “If they could’ve, they would’ve,” says George Friedman, a former Pentagon advisor who now runs an Austin-based private intelligence company called Stratfor. Friedman says the legions of cyberterror “experts” are little more than storytellers. “They love technical head games, but ask them to point at really successful attacks on critical infrastructures and they’re at a loss,” he says.

It’s true that there’s nothing cyberterror buffs enjoy more than pointing out vulnerabilities and bragging about how they could exploit them. Howard Schmidt, former security chief at Microsoft and now the deputy chairman of the President's Critical Infrastructure Protection Board, was reminded of this professional pride this summer, when he told an assembly of computer engineers that in all his years in the field, he himself had never been a victim of computer crime. “Is that a challenge?” hollered a consultant in the crowd. “We have the technology.”

The room erupted. And the laughter wasn’t just at the expense of an easy target like Schmidt. It hit on an obvious but rarely-spoken truth: that most of us will never encounter even a petty thief online, but that the creators of the most devilish cyberterror scenarios are right here among us, designing software, writing techno-thrillers, and setting government policy. And they’re scaring us silly.

“We’re all sitting around looking in the mirror, asking if someone was just like us, how would he take advantage of our weaknesses?” says Fred Freer, a retired CIA analyst and specialist in the Middle East. “Of course they’re not just like us. We’ve got to get out of this crazy reactive mode and stop trying to scare ourselves. We’re all chasing our tails and looking more and more foolish.”

more

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment