In finance, a hedge is a position established in one market in an attempt to offset exposure to the price risk of an equal but opposite obligation or position in another market — usually, but not always, in the context of one's commercial activity. Hedging is a strategy designed to minimize exposure to such business risks as a sharp contraction in demand for one's inventory, while still allowing the business to profit from producing and maintaining that inventory. A typical hedger might be a farmer with 2000 acres of unharvested wheat in the ground, who would rather tend her crop without the distraction of uncertain prices. She's a farmer, not a speculator, yet her unharvested "inventory" may have lost 35% of its value ($285,000) in the three months she's been planning her planting. She might have decided she could live with a price of only eight or nine dollars a bushel, and to offset her planted position with an approximately equal but opposite position in the market for wheat on the Minneapolis Grain Exchange by selling ten wheat futures contracts for December delivery. This farmer is thereby a hedger indifferent to the movements of the market as a whole, and has reduced her price risk to the difference between the price she will receive from a local buyer at harvest time, and the price at which she will simultaneously liquidate her obligation to the Exchange. Holbrook Working, a pioneer in hedging theory, called this strategy "speculation in the basis,"[1] where the basis is the difference between today's market value of (in this example) wheat and today's value of the hedge. If that difference widens, she earns a little more at harvest time. If that difference narrows, she earns a little less. She has mitigated, but not eliminated, the risk of losing the value of her wheat as of the day she established her hedge.

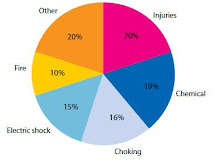

Some form of risk taking is inherent to any business activity. Some risks are considered to be "natural" to specific businesses, such as the risk of oil prices increasing or decreasing is natural to oil drilling and refining firms. Other forms of risk are not wanted, but cannot be avoided without hedging. Someone who has a shop, for example, expects to face natural risks such as the risk of competition, of poor or unpopular products, and so on. The risk of the shopkeeper's inventory being destroyed by fire is unwanted, however, and can be hedged via a fire insurance contract. Not all hedges are financial instruments: a producer that exports to another country, for example, may hedge its currency risk when selling by linking its expenses to the desired currency. Banks and other financial institutions use hedging to control their asset-liability mismatches, such as the maturity matches between long, fixed-rate loans and short-term (implicitly variable-rate) deposits.

A hedger (such as a manufacturing company) is thus distinguished from an arbitrageur or speculator (such as a bank or brokerage firm) in derivative purchase behaviour.

Contents[hide] |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment